Esperanto: hearings before the comittee of education

Fig. 1: Unknown maker. 1952. 1952 Oslo Norway World Congress Esperanto International Stamp Collector’s Cover [paper, ink]

In my research on Esperanto I came across the transcript of a hearing before the comittee of education in USA, from 1914. In the hearing, Professor A. Christen (writer of From Babel to Esperanto, who I haven’t been able to find much more information about) gave a detailed statement on why Esperanto should be taught to American school children. One of the areas I’m looking into as a way of democratising Esperanto is ways of introducing it to the Norwegian school system. Thus, Christen’s arguments were very valuable.

A symbol of welcome

Christen starts his hearing by pointing to various publications in Esperanto, such as tour guides and other information leaflets, explaining how they are “for the use of foreigners and tourists” (Christen, 1914). This made me think about a comment from our panelist review, where Freuke mentioned how a visual language in the streets could comfort immigrants by making them feel welcome.

In a hypothetic scenario where everyone knows Esperanto, portraying information in both Norwegian and Esperanto would say “foreigners are welcome”. The usage of the language symbolises openness and inclusivity. “If you know Esperanto, you shall not be a foreigner anywhere” (Christen, 1914).

Esperanto in schools

Further, Christen argues that Esperanto should be taught to children from 5 years of age, not only to increase knowledge on Esperanto, but because knowing the language would help children learn English (Christen, 1914).

This made me think of the various opportunities for schools if every school in the world would teach Esperanto. Pupils could adopt correspondence as part of the curriculum, and could potentially visit any country in the world and understand what that country’s pupils were saying. This could be a great way of learning about various cultures and people who are different from oneself.

Gathering insight on language in Norwegian high schools

In order to understand more about language offers in the Norwegian school system, I got in touch with the person in charge of Chinese at one of the Oslo high schools. The school offers Chinese as one of the mandatory language classes, and I wanted to understand how that had come about.

Why does the school offer Chinese?

Through our conversation I learned that several years back, the high school had had a drop in applications, leading to them wanting to make a change in their communication and offering. They decided that the school should be “something more” – which became part of their way of running the school. A few years later this led to them wanting to put up Chinese as one of the language classes. At this time, China had a huge industrial arising, and their relationship with Norway was very good. Thus, the school’s reason for offering Chinese in the first place, was both beneficial in terms of school strategy and the political agenda at the time.

Motivations for choosing Chinese

We then went on to discuss students’ motivation for choosing Chinese as one of their classes – to which I was made aware of five main categories:

1. Connections to China

Some students are either from China, or they have some type of connection to the country.

2. Business advantage

Most students who take Chinese have high ambitions when it comes to career and further studies. By doing Chinese, they are able to differentiate themselves from other applicants, giving them an advantage in their soon to come work life. Several of the pupils who has taken the class has been given Chinese scholarships at China’s top 10 universities – studies that are normally very hard to get in to. This second motivation is very pragmatic, and demonstrates how some students make tactic choices of language classes.

3. Study trip at the end of the class

All pupils that finishes the three mandatory years of Chinese get to go on a study trip to China, where they get to live with Chinese families and go to a Chinese high school. This is one of the most important motivations, and demonstrates the pupils’ lust for adventure and community.

4. A new beginning

Before high schools, pupils have already had a third language such as French, Spanish or German. By doing Chinese they get to start fresh – they get a second chance at succeeding with language class.

5. Play, sound and drawing

Chinese is a visual and aesthetic language. It offers a new way of working with culture, where one has to learn to form the letterforms, and listen to new sounds. Many students resonate with this visual approach to language. Since Chinese is completely different to Norwegian and English, students get to take a more playful approach, where they focus on listening and doing calligraphy, starting at a very basic level of difficulty.

The notion of approaching learning with play, visual exploration and sound is very interesting to me, and perhaps the motivation I can work with to the largest extent in terms of using design. Esperanto is very different to Chinese in terms of these points (it is based on Romantic languages, uses the Latin alphabet and will be very familiar to students). However, I think there’s a real opportunity of introducing creative aspects to the curriculum, by connecting the language to it’s ideologic essence.

Making Esperanto part of the system

My interviewee suggested the following steps if wanting to create an Esperanto high school class:

- Find a new school that is looking to develop a niche language class

- Apply for funding and do a test programme

- Hire the world’s best and most inspiring and engaging Esperanto teacher

- Present the class with selling arguments for choosing the class

- Find a cool country (since Esperanto is not state-connected one can go pretty crazy here) that the pupils will go on a study trip to. after finishing the three year class

The importance of marketing

Although students have various motivations for choosing Chinese, my interviewee also explained how important the marketing of the class is. After all, if you don’t get applicants, you won’t be able to finance the class.

Word of mouth

The most importing marketing factor, according to my interviewee, is that older pupils speak highly of the class to their siblings or other younger people. For this to happen, the actual class needs to be motivating and fun to attend.

The idea behind Esperanto

My interviewee suggested that since knowing Esperanto doesn’t currently give you any advantages in business, one would need to market the class by focusing on the ideology/idea behind Esperanto. As an example he mentioned that another Oslo high school offers sign language, which has been very popular. He argued that this popularity stems from the fact that pupils are concerned with equality and non-discrimination.

This showed me that in fact, the idea behind Esperanto is already engaging youth today (a universal language based on the idea of inclusion). Thus, I could either make it my aim to present Esperanto through it’s ideology, or I could simply use sign language instead of Esperanto, as this is in fact more including. One approach to using sign language could be to explore how a universal typeface/writing system could be developed – so that sign language could become a non-political language in the same way as Esperanto.

Esperanto and Its Rivals: The Struggle for an International Language

Wanting to make sure that I knew as much as I could about Esperanto before proceeding to ideation, I went through the book Esperanto and Its Rivals: The Struggle for an International Language.

The author, Roberto Garvía, argues that there are two ways that a language can become a lingua franca:

- An international body can adopt it formally

- The strength and extension of it’s community makes it so

(Garvía, 2015)

This means that in my project, I can either target international policy makers, or aim to build a community of Esperanto speakers. Following upon my prior language, I believe the latter will be most relevant – particularly if choosing to target youth.

Why not English?

In his book, Garvía mentions that all international languages through history (Greek, Latin, Arabic, French and English today) have become so due to imperial prestige (Garvía, 2015). Therefore, making these languages the international standard would be “to extend the power of that nation or race, however impartial might be the intentions” (Garvía, 2015). Garvía argues that if party A speaks the chosen language fluently, whilst party B speaks it as a second language, party B will not be able to express themselves as fluently, accurately and convincingly as party A (Garvía, 2015). Thus, party A will have a better position at the negotiating table (Garvía, 2015).

Here, Garvía’s makes a great argument for my project’s aim – why we should be promoting Esperanto as a language to be taught to all. His reasonings are not new views in terms of my project direction, but will be useful in my report as I go to argue for Esperanto as a solution to the language hegemony issue.

Esperanto’s inner idea

Although I have explored the ideology behind Esperanto previously, Garvía provided more detailed information on what Zamenhof thought of as “the inner idea of Esperanto” (Garvía, 2015. To Zamenhof, Esperanto was a tool which was to stop ethnic hatred by “establishing a linguistic and religious common ground that could help individuals recognise one another’s humanness” (Garvía, 2015).

This common ground between people is what fascinates me about Esperanto, and it would be great if my project could be about building this common ground – a bridge to help various people connect. In terms of design, this could involve an exhibition or workshop, getting people to send postcards to each other, building a website where people could “tell their stories”, or simply redesigning the visual identity and marketing strategy of the Esperanto Oslo department (where the aim would be to attract more people).

Garvía further explains how Zamenhof defined the inner idea as “the pursuit of peace and mutual respect among ethnic and national groups” (Garvía, 2015), and according to Zamenhof, Esperanto was “a constant celebration of humanity and human brotherhood” (Garvía, 2015.

Peace, humanity and brotherhood are all great keywords for my further development. They could either inform any visual translation of the language, or I could explore user generated design solutions.

A democratic language

On the notion of user generated design, Zamenhof’s thoughts on grammatical rules and vocabulary becomes interesting. He suggested that although Esperanto had some foundational grammatical rules established, the language belonged to its community, and communication between the people of the community was the priority, rather than an absolute correct language (Garvía, 2015). It was up to the community to decide on any disputes (Garvía, 2015).

Democratic design solutions have been of huge interest to me in prior projects, and I think it would be great to bring this into this project as well, as it links so well with Zamenhof’s vision for Esperanto. One idea based on the above would be to develop a type of democratic dictionary, open for changes performed by the Esperanto community. However, it could also be interesting to focus on user generated visuals as discussed above.

Audience

Garvía also discussed the demographics of Esperantists in his book, which is useful when it comes to analysing my audience. A range of various groups joined the Esperanto community, including catholics, protestants, socialists, pacifists, vegetarians, excursionists, but also photography aficionados and stamp collectors (Garvía, 2015). According to Garvía, Esperantists with an ideological motivation where the ones who were most involved in the movement.

To me, the common factors that join these groups are the want for common good and the urge to fight for one’s beliefs. This tells me that I should be targeting the activists in Norwegian society.

Esperanto has also been popular amongst the blind (Garvía, 2015). Since the production costs of printing in Braille are quite high, having a universal language would make literature more available, as it would cause a higher demand for each book. Including the blind and the deaf would be very useful for my project, since inclusion of all is basically the foundation of Esperanto.

Successes and failures

In order to solve my research question (How can Esperanto be democratised, in order to help the language achieve it’s original purpose?, which perhaps could be changed to How can Esperanto become the lingua franca and achieve it’s original purpose?), I will need to understand it’s failures and successes, so that I can avoid any prior mistakes, and build upon the wins.

Esperanto’s successes

According to Garvía, the (small) success of Esperanto comes down to it’s foundational ideas of peace, justice and mutual respect (Garvía, 2015). He further suggests that like the QWERTY keyboard and VHS, Esperanto did not succeed because of it’s technical benefits, but due to organisational factors and ideology (Garvía, 2015).

This tells me that in my work on making Esperanto the lingua franca, my main focus should not be on how easy the language is to learn or on the quality of it’s construction, but rather on the ideologic concept – the “inner idea” of Esperanto.

Why did Esperanto fail?

Garvía suggests that all lingua francas to this date, owes their success to the economic and political power of their speakers (and their states) (Garvía, 2015). Since Esperanto is stateless, it has never had a government that holds this power (Garvía, 2015). Nor has it had acceptance from the general public (Garvía, 2015).

According to Garvía, Esperantists “had to strive for the recognition of an outside and not very sympathetic world” (Garvía, 2015). In many ways this quote demonstrates the dilemma of a universal language (and by effect, united agreement in general). The world is not black and white, and it’s peoples will never be able to agree on everything. Thus, I come back to a prior conclusion – that Esperanto will always be a symbol of common good, rather than an actual solution to world conflict.

We need to feel our language

Going back to the very beginning of this project, I explored how a language could be felt, looking at how the Maori people in Australia could not “feel their language” in the city. In his book, Garvía claims that there is a mysterious link between language and ethnicity, and that because of this, artificial languages can never truly succeed (Garvía, 2015). He further quotes the prior European Commissioner for Multilingualism, Leonard Orban; “Esperanto is lacking culture, and therefore not a real language” (Garvía, 2015).

Although that after learning about Esperanto, I would definitely claim it has culture, I can understand how there is a missing link between one’s own identity and Esperanto. Therefore, I think an important aspect of my project will be to build the culture of Esperanto – and to make speaking the language into an act of purpose. Esperanto will have to be made into something we can feel, perhaps through the establishment of visual and ideological culture.

Interview with an Esperantist

In order to back up my research I wanted to talk to an Esperantist before moving on ideation. Through a conversation with an Esperanto speakers, I got to discuss how recruitment of Esperantists and what the value of the language is today.

The Esperantist explained that for him, the language has been used when travelling, thanks to the international community, which often accept travellers into their own homes. In terms of making Esperanto a lingua franca, he explained how this lies in the distant future. He didn’t seem to believe that making Esperanto a lingua franca would solve the world’s conflicts.

In terms of recruitment, he explained that this can be difficult, and that they have focused on getting press (although this doesn’t happen regularly), handing out flyers and talking to friends. This tells me that they might benefit from a marketing strategy which would let them reach out to more people.

When asked about my “making Esperanto part of the school system” idea, the Esperantist was very positive, suggesting that that is a good route to go down.

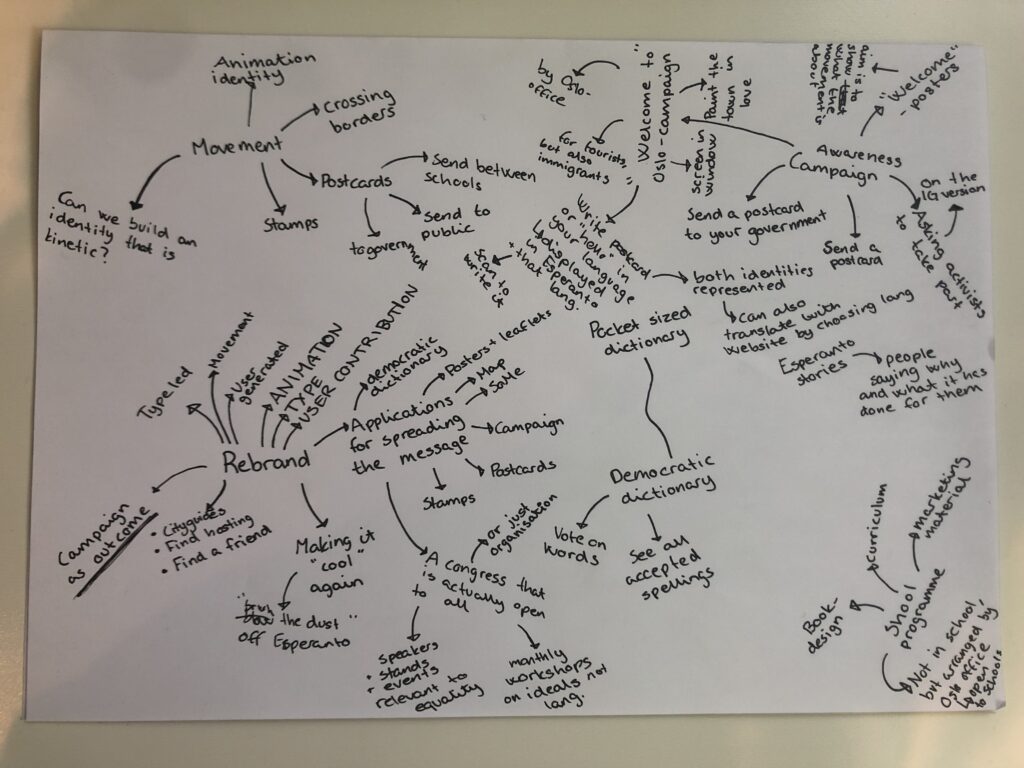

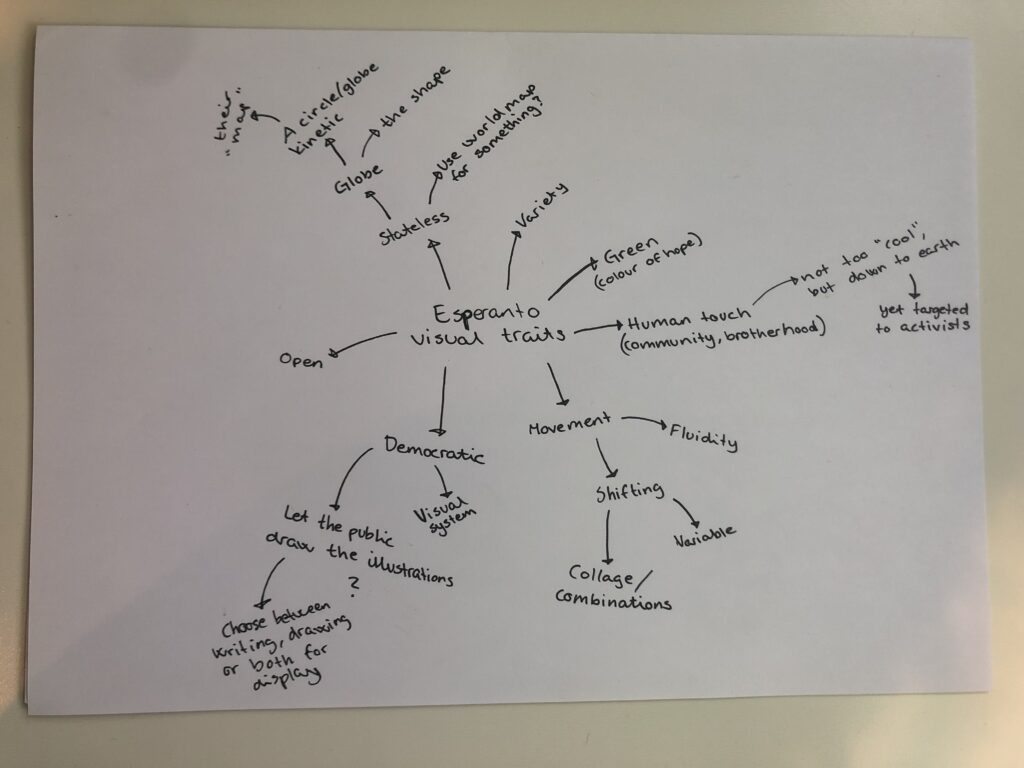

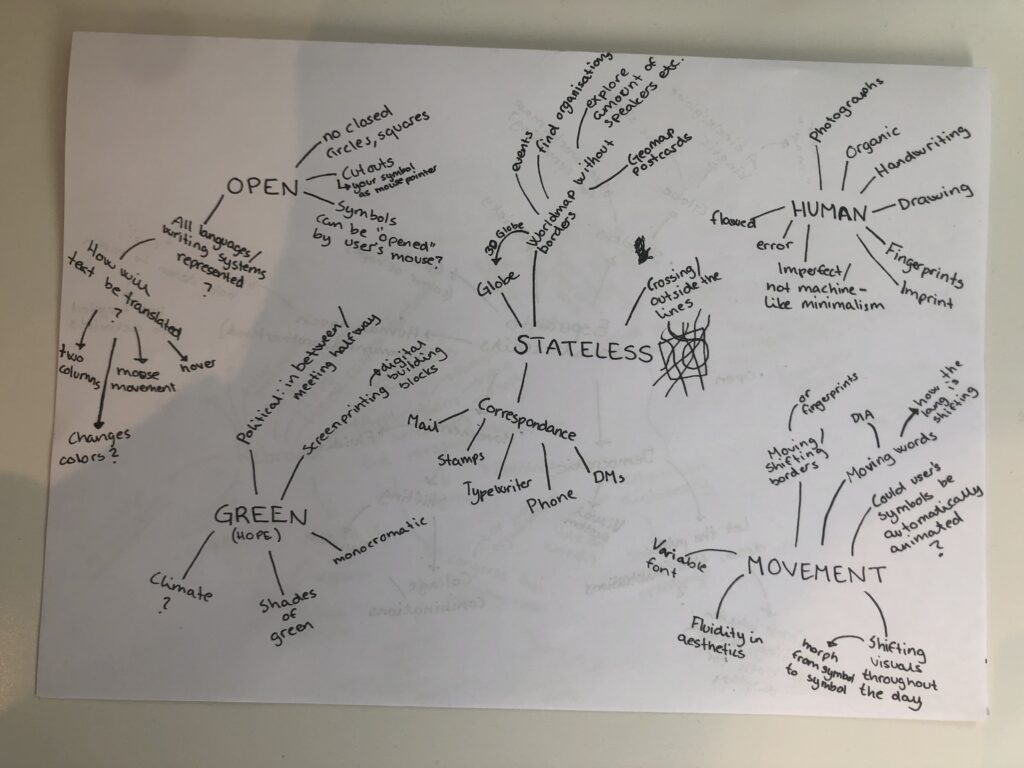

Design development

Having spent a long time on my theoretical research, it was finally time to embark on my design development. I kickstarted the process with some mindmapping. This helped me form a vague idea of what I was actually going to make.

Initial ideas

Below are some of the format ideas I came up with:

A rebrand of Esperanto

In my interview with the teacher, my interviewee mentioned that no one really cares about Esperanto today. This is a subjective opinion, but I have to say that this is also my impression of the general public’s stand. A rebrand of Esperanto organisations might help brush the dust off Esperanto, making it relevant for today’s audiences. The rebrand doesn’t necessarily have to be a solely visual project, it can also tackle some of the issues the Oslo organisation is having today (recruitment and gaining press).

Awareness campaign

In order to really brush the dust off Esperanto, I believe an awareness campaign would be the right format for my project (this would most likely be an extension of the above). This could take place on social media (posting activist quotes in Esperanto, getting music artists or authors to publish work in Esperanto, etc.), or it could be more physical in the shape of posters and stands.

Correspondence could be a keyword here, as this reflects the act of crossing borders. Perhaps I could use postcards, DMs or stamps as outcomes, getting the public to take part somehow?

During the panel review, Frauke mentioned that it would be nice to welcome non-Norwegians to Oslo, using design. It would be great to do a “welcome to Oslo”-campaign, using Esperanto, as this would be in line with the inner idea of Esperanto. This could be done using visual posters and marketing material – or it could be a stunt, for example by letting people come and stay with the Esperantists in Oslo.

Democratic dictionary

Inspired by the fact that Rhodes thought the Esperanto dictionary had to be convenient to use, in order get the public’s acceptance, it would be fun to do a convenient Esperanto dictionary today. Esperanto is already part of Google Translate, so in order to add value beyond normal translation, it could be interesting to look at democratic functionality.

Zamenhof meant that although Esperanto had a set of foundational grammatical rules, the language belonged to its community, and therefore the community should be in charge of deciding on any linguistic disputes (Garvía, 2015). The process on deciding on linguistic disputes could be the focus of this “democratic dictionary”.

This idea is perhaps not the most relevant if my aim is to make the general public aware of Esperanto. However, it would be a great project in terms of my personal interest, because a dictionary could be a wonderful format for typographic works. Maybe the letterforms could change based on acceptance of a linguistic alternation?

School programme

A service design approach to my project could be to develop an Esperanto school programme, based on insights from my teacher interview. For this I could develop the school programme/curriculum (based on Esperanto’s inner idea as well as linguistics), marketing material, and book designs. During the Esperantist interview, my interviewee mentioned that making the language part of the school system would be the right way to go about my project, and this idea is thus perhaps the most relevant in terms of real probability.

Feedback summary

Before going ahead with any of the above ideas, I wanted to do a summary of all my gained feedback so far, in order to make sure that I was responding to it (the points that were still relevant at this stage).

Panel review feedback:

- Scout suggested that my project might be an opportunity to lift others’ voices, instead of inserting ourselves in a perspective that isn’t ours. This might be relevant if I choose to focus on “the hybridisation of cultures” – an approach that could be very relevant for Esperanto.

- Frauke mentioned that having to speak a new language can make you feel vulnerable, and in order to share your vulnerabilities you have to be comfortable and engaged. Therefore, developing messages for non-Norwegians could make them feel as if someone is looking out for them. This notion of welcome/comfort is very much in line with the inner idea of Esperanto, and something I’ve already considered in the above awareness campaign reflections.

- We also discussed how nationalism can sometimes be forced upon immigrants. Rather than “Norwegianising” people who come to Norway, we should work on developing a hybridisation of cultures, particularly because this seems to be the core of Esperantist values.

I was also advised to use workshops and user generated design methods in my project, in order to approach my topic with empathy. Although I saw this as hugely relevant for the project at the time, I have now moved on to a more focused direction where Esperanto is the main topic, rather than immigration (a more sensitive and human centred topic). I might still want to include user generated design in my outcome. However, I no longer see it as vital as empathy is not as huge a part of my project as it was.

Feedback and insight from my interview with the person in charge of the Chinese course at one of the Oslo high schools:

- The current political situation can determine what languages schools choose to put on as courses. Although Esperanto is not currently having it’s prime time in terms of popularity, the language is indeed very relevant because of the political challenges we are facing (agreeing on climate change solutions, refugee crisis, equality getting addressed in various environments and situations, etc.).

- Young people seem to be more open to learning a language if the teaching methods revolve around play, sound and drawing (in other words, by using a varied and creative teaching approach). Of course, high schools student have to choose one language, so if Esperanto is not part of the school system, we can not be sure that this point will be relevant, unless they are looking for a new language to learn. This indicates that my audience should be activists – people who are looking ways to take action – as they might have more of a drive to go out and learn Esperanto.

- My interviewee suggested that since knowing Esperanto doesn’t currently give you any advantages in business, one would need to sell the ideology/idea behind Esperanto. The sign language course in Oslo has been very popular, and the interviewee argued that this popularity stems from the fact that pupils care about equality and non-discrimination. These topics sit at the core of Esperanto, and should be communicated in my outcome.

- Lastly, my interviewee did not have faith in Esperanto as a high school course. He argued that Esperanto could not defeat English as an international language, that it’s too niche, and that people aren’t interested in it anymore. This merely tells me that Esperanto needs an upgrade, and that we need to make people aware of Esperanto and the (I think very cool) idea behind it.

Insight from interview with Esperantist:

- Recruiting new members has proven to be challenging.

- Their recruitment methods consists of trying to get attention from the media, handing out flyers in the street and talking to friends and family about Esperanto. They also send out physical “news letters” on a regular basis, updating Esperantists on what they have been up to.

- The interviewee has personally had very pleasant experiences when going abroad to stay with Esperantists. He found these people/homes in a list that they keep, of people who are happy to take in Esperantist travellers to their homes. This list could be expanded on as it resonates with contemporary travelling concepts such as couch surfing and Airbnb

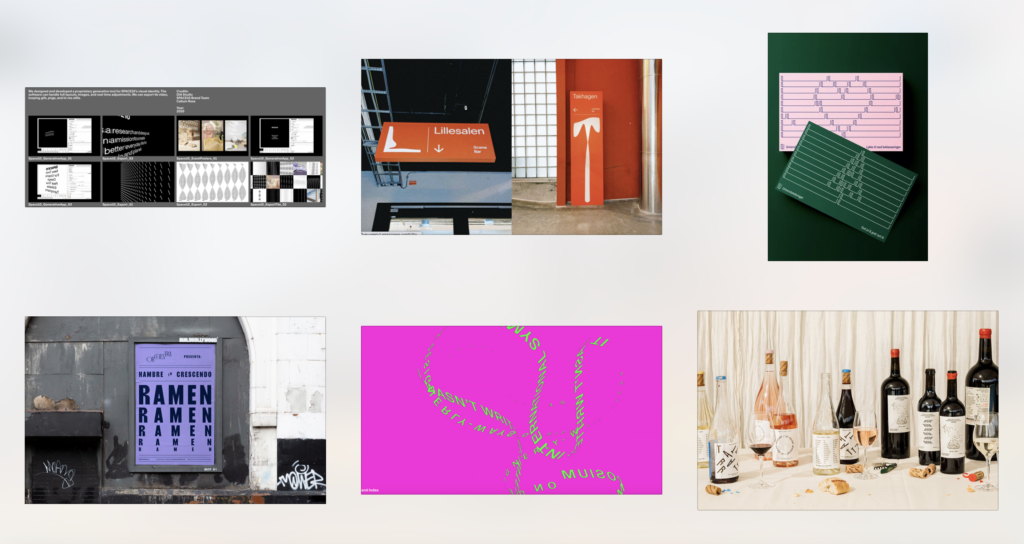

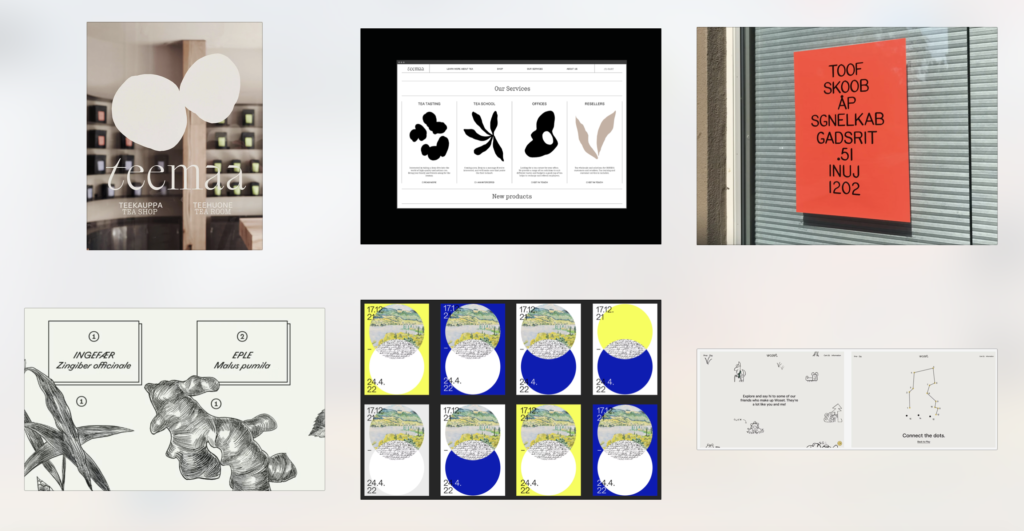

Case studies that I love

In order to gain some design inspiration I also wanted to explore case studies I love. These are not necessarily relevant to my topic, but rather inspiring in terms of design and technology.

Fig. 3: Gaupset 2018. Fonograf. [typeface]

Benjamin Gaupset: Fonograf

Fonograf is a typographic project by Benjamin Gaupset, inspired by phonetic symbolism (a theory based on there being a link between a word and the thing it describes). What I love about this project is how it combines linguistic theory, technology and typography. It’s fun, but also makes you think about the core linguistic concept, which I personally enjoyed reflecting on. The outcome is not useful at all, but rather design for design’s sake. Since the MA project is my last uni-project it’s tempting to explore a similar solution, simply because I will most likely be doing “useful” design for the rest of my career. If choosing to explore the democratic dictionary route, I could potentially take a similar approach to Gaupset. I am however slightly hesitant to go down this route because it doesn’t really argue for learning Esperanto (it would be design for design’s sake and not convince the audience to learn the language).

Heydays.no

From what I can tell, design studio Heydays’ website is based on their explorations into how natural aesthetics can be implemented in digital design. In their medium article on these explorations, they go into “how we can use principles of natural light when designing for a glowing screen” (Heydays, 2022). I love how this project is deeply rooted in aesthetics, but doesn’t explore any of the typical design elements (typography, logos, etc.). Perhaps in my project I could use design and technology to explore the concept of hybridisation of cultures, rather than a typical learning platform or poster campaign? This could for example be a platform of Esperanto resources, based on brotherhood and culture sharing. If doing the demographic dictionary for example, the intention could be to develop Esperanto into a true reflection of all languages, rather than solely romantic languages, using user contribution. Users could also contribute to culture making, using drawing, sound etc.

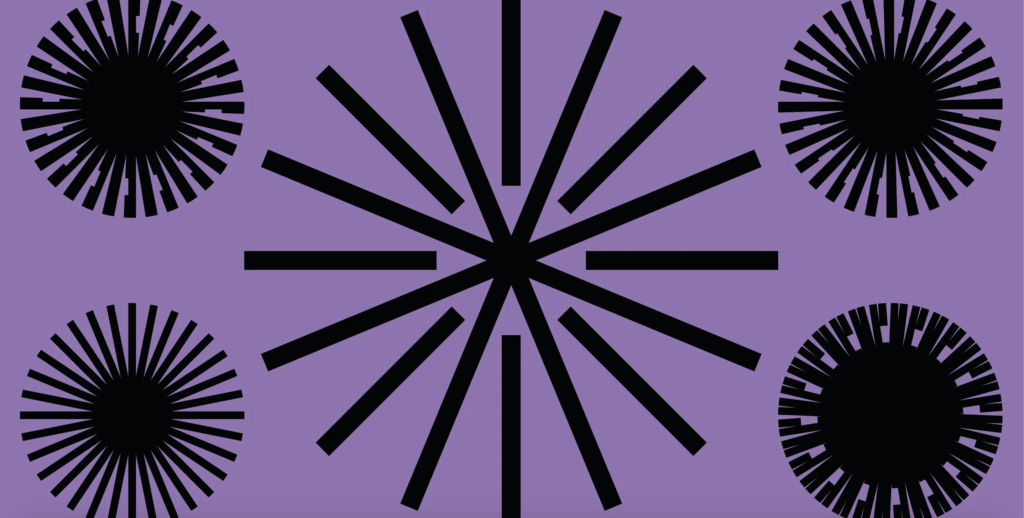

Studio Lowrie: Visual identity for the Sundance film festival

I’ve looked at this project many times during the time of this course. It’s one of my favourite graphic design case studies and I love the simplicity, energy and drama it holds. In terms of my project, the symbols are very relevant, as I believe a symbol logo would be in line with the international organisation nature of Esperanto (organisations such as EU, UN, etc. all have strong symbols as logos). A symbol is also relevant because it connects to the symbolism of flags – a symbol could become the flag of the statelessness of Esperanto. Lastly, a symbol is more international than typography, as it’s legible for non-latin writing system readers. Perhaps this symbol could be user generated somehow?

Bleed studio: Visual identity for Avo Consulting

Speaking of symbols, this visual identity is interesting because it has replaced two logo letters with icons. Although I’m tempted to focus on typography in my project, it will be important to reflect on how the latin alphabet is not really inclusive beyond the Western world.

Descriptive words and moodboards

In my prior mindmap session I established a set of descriptive words for Esperanto, which would guide my visual process moving forward. In order to process these thoroughly I went on to do a new mindmap for the words, and to develop accompanying moodboards for each of them (see Formative assessment outputs for moodboards).

Although I have a set of varied ideas that I’m considering for my project, I think these descriptive words could be used for all of them (in terms of visual development).

Formative assessment outputs

Report draft

I have not prioritised to document the process of writing my report, as this was merely a question of gathering my literature research, as well as arguments stated in this and previous blog posts.

My current report draft can be viewed here.

Action plan

My action plan for phase 4 can be found here.

Design ideas (development)

Over the next two weeks I’m planning on testing the following 4 ideas, for then to choose one I will be going ahead with:

Esperanto culture making

Garvía discussed how Esperanto can never succeed as a lingua franca because it lacks a culture (Garvía, 2015). In order to build and expand on Esperantist culture, I think it could be great to build a platform for Esperanto culture making. Here I would explore how we can develop a hybridisation of cultures, in the same way that the language is a hybridisation of languages. The culture building could consist of physical workshops and events, but I’m mainly interested in developing a digital platform where users would generate their own content. Perhaps they would draw or write something, which would then be paired with content developed by other users. Or perhaps they can create their own symbols for Esperanto’s new logo (which is then showcased on the website). The user generated outcomes should be showcased somehow (on t-shirts or prints, on the actual website, on a physical installation, or something else). The essence of this idea would be to demonstrate that Esperanto belongs to its community, and that it’s a matter of stepping out from your own culture in order to meet half way.

Standard rebrand of Esperanto

This is a more classic approach to my project, where I would simply work on visually translating the inner idea of Esperanto into a visual identity. The aim would be to brush the dust off Esperanto, making it appeal to the audiences of today. Part of me wants to start off with this idea and see where it takes me, as it could later be expanded into one of the other ideas if I have enough time.

Awareness campaign: Welcome to Oslo

This idea would be inspired by Frauke, who discussed how it would be nice for immigrants to be welcomed to Oslo by visual languages, as it would mean that someone is looking out for them. This could entail workshops with non-Norwegians, resulting in a more user centred direction than I was hoping to take. A Welcome to Oslo campaign could also be simple posters, stands or events, saying “welcome” in Esperanto (more of a typographic project than a user generated one).

Democratic dictionary

Zamenhof thought that Esperanto belonged to its community, and that they should be in charge of deciding on any linguistic disputes (Garvía, 2015). The process on deciding on linguistic disputes could be the focus of this democratic dictionary. The platform could also be a tool with an aim of improving Esperanto, finding the most common word for every concept that there is a word for across all languages (rather than solely Western, as done by Zamenhof). If we could generate the most frequently used word for each concept there is a word for, we might be able to generate a new Esperanto vocabulary, to be used by modern Esperantists. The words could either be computer generated, or they could be suggested and voted on by users (which would be less “correct”, but more in line with typical democratic processes).

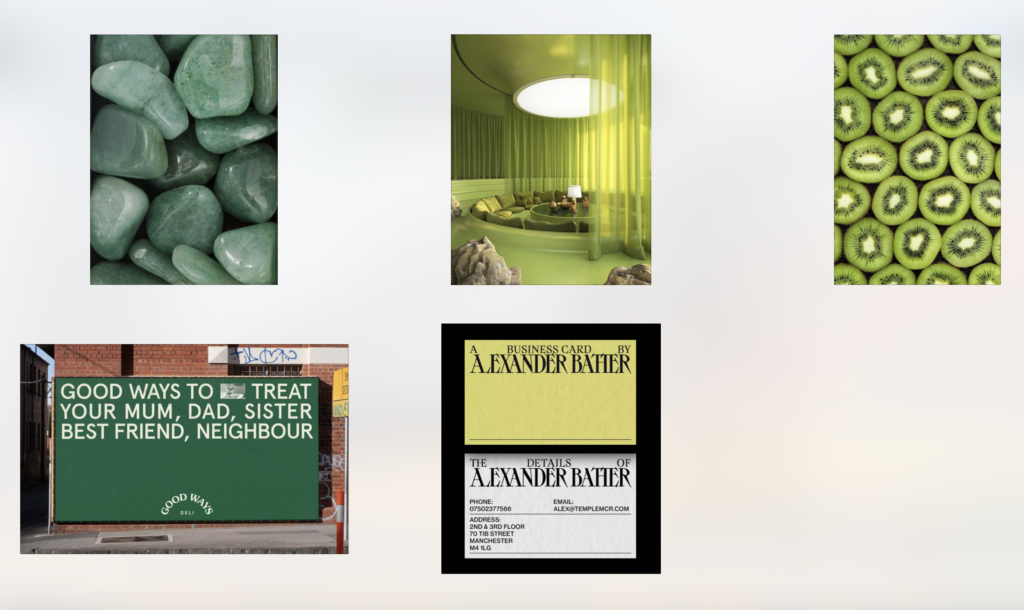

Moodboards:

I am yet to do any visual design development for the ideas, but below are moodboards for my five descriptive words, which will inform the visual development for the above ideas:

Movement:

Green:

Human:

Open:

Stateless:

In conclusion

These weeks have been really valuable in terms of finally deciding on a clear direction. I have managed to do two interviews and also to collect valuable insight from literature, which has helped a great deal with the critical report. I’ve enjoyed diving into the history of Esperanto, but I am also excited to step away from the books and enter the design phase.

Looking back at the three stages I’ve gone through so far, I think I should have spent a great deal more time on designing and experimenting, as this would have helped me reach the goals for phase three (presented design tests and development). However, I am also glad in a way, that I let myself remain in the research phase as this has helped gain a true understanding of Esperanto and it’s inner idea. The fact that I managed to step away from an idea that wasn’t working (developing my own language) has also been good as I feel much more confident in my current direction.

In phase four I will get straight into design development, as I move on to test and experiment with my project ideas. I think it will be important to jump right into visual development, as this has felt a bit scary up until now. I look forward to being visual again, and to finally get into some type work.

REFERENCES:

Christen, A. (1914) Esperanto: Hearings before the Committee on Education, Gutenberg.org. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/16432/16432-h/16432-h.htm (Accessed: 29 April 2022).

Garvía, R. (2015) Esperanto and Its Rivals : The Struggle for an International Language. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Heydays (2022) ‘Aesthetics for health and happiness in brandsand digital design’, Medium, 13 April. Available at: https://heydays.medium.com/aesthetics-for-health-and-happiness-in-brandsand-digital-design-1c775b306fa2 (Accessed: 26 May 2022).

LIST OF FIGURES:

Figure 1. Unknown maker. 1952. 1952 Oslo Norway World Congress Esperanto International Stamp Collector’s Cover. [paper, ink]. Ebay [online]. Available at: https://www.ebay.com/itm/163768441094 [accessed 28 May 2022].

Figure 2. Unknown maker. 2015. Esperanto and Its Rivals: The Struggle for an International Language. [book cover]. Akademika [online]. Available at: https://www.akademika.no/esperanto-and-its-rivals/garvia-roberto/9780812247107 [accessed 28 May 2022].

Figure 3. Benjamin GAUPSET. 2018. Fonograf. Benjamin Gaupset [online]. Available at: https://benjamingaupset.com/fonograf/

Figure 4. HEYDAYS. 2022. Heydays.no. Heydays [online]. Available at: www.heydays.no

Figure 5. STUDIO LOWRIE. 2020. Sundance film festival. It’s Nice That [online]. Available at: https://www.itsnicethat.com/features/studio-lowrie-sundance-film-festival-2020-identity-graphic-design-240320a

Figure 6. BLEED. 2019. Avo consulting. Bleed Studio [online]. Available at: https://bleed.com/avo-consulting

Figure 7: Ingrid REIGSTAD. 2022. Moodboard: Movement. Private collection: Ingrid Reigstad.

Figure 8: Ingrid REIGSTAD. 2022. Moodboard: Green. Private collection: Ingrid Reigstad.

Figure 9: Ingrid REIGSTAD. 2022. Moodboard: Human. Private collection: Ingrid Reigstad.

Figure 10: Ingrid REIGSTAD. 2022. Moodboard: Open. Private collection: Ingrid Reigstad.

Figure 11: Ingrid REIGSTAD. 2022. Moodboard: Stateless. Private collection: Ingrid Reigstad.