Lecture notes

Lecture reflections

Martin Hosken: The theory and symbolism behind a message

The fact that meaning is culture- and context specific is quite interesting to me (Hosken, 2020). As designers, communication could perhaps be described as an ideal result of our works, and so we must ensure that our message is in fact being communicated. Hosken’s point on the emoji was a fun anecdote as I find what he said very true. I often feel that the emoji can communicate feelings which is hard to convey through words, and it seems to me that this concept is also relevant in graphic design. Through image, text and sound, we are able to communicate in a perhaps more effective way, than we would by simply writing the message out using letters.

Hosken’s lecture provided a clear and easily understood summary of semiotics and the terms that belong within the study.

Tom Finn: Taking graphic design today and unpacking it. Take one story to see how it is reported globally

I loved seeing the various Olympics identities and how they utilise branding systems in a variety of ways. To me, the comparison between the first London Olympics branding, and the recent one by Wolff Ollins (Finn, 2020), was particularly interesting as it demonstrated the importance of cultural knowledge in communication (Finn, 2020). This opened my eyes to the various need for literalness in a design. The amount of information needed is hugely based on the receiver’s understanding and previous knowledge on the context. Thus, a designs ability to communicate is hugely dependant on it’s audiences cultural understanding on it’s topic and context.

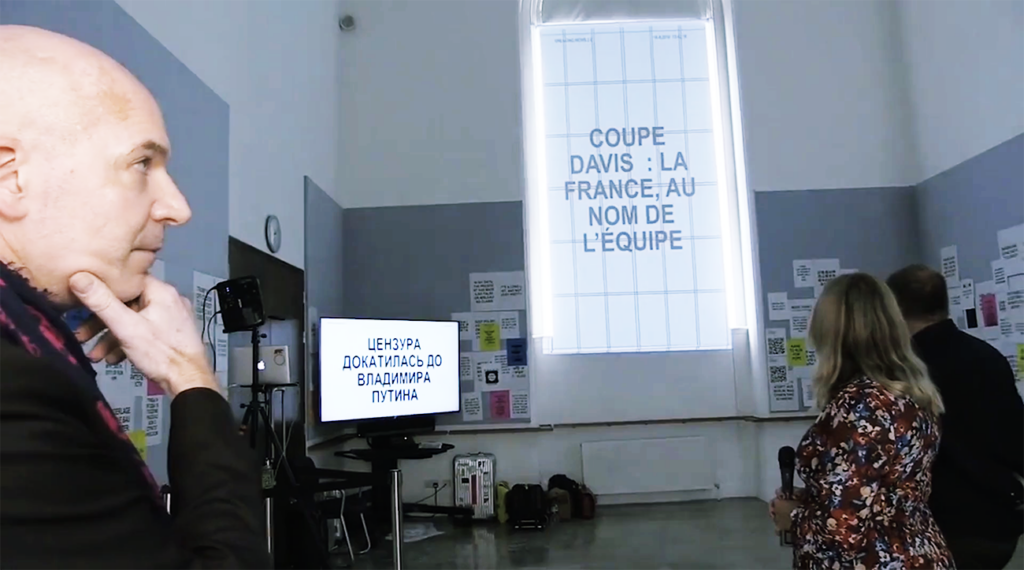

Susanna Edwards & Patrick Thomas: Breaking News 2.0 Installation at the London Design festival

Bearing in mind my previous point on the amount of information / cultural understanding needed, in order for a message to be communicated, Breaking News 2.0 becomes interesting. The very basic cultural understanding of letter systems for example, is needed in order to understand the variety of messages portrayed in the exhibition. If one does not understand Russian letters (nor the Russian language), one can simply not receive the Russian messages. Further, the receiver must have a cultural understanding of several other aspects in order to understand the messages, such as knowledge about basic social aspects, current news, and perhaps the backgrounds for the submitted texts from the exhibition’s visitors.

The shapes paired with the texts were interesting and I liked how they were meant to add meaning to random texts (Edwards and Thomas, 2020). This says something about how we intemperate messages based on how they are projected, implicating that there’s usually not one truth, but simply perceptions on various phenomenons. Our view on the world is hugely based on the journalists of our news platforms – thus the thought of them being manipulating becomes quite frightening and existential.

Resource notes

Resource reflections

Visible signs: an introduction to semiotics in the visual arts

Understanding the reader

In terms of branding, I think it’s important to understand the semiotics of the way signs are organised within a system, and thus, the meaning of them. Further, I think it’s important to remember that of Pierce and Barthes, that meaning of signs are constructed by those who reads them (Crow, 2010). In order to ensure that communication is happening, we must understand how our audience reads meaning from our designs. In other words we must know our target audience and what it is they know, in order to ensure that they understand and like our design.

Maintaining ambiguity

Further, I think we as designers can benefit from being aware of relay and anchorage. Although it might be preferred in certain contexts, Barthes claims that anchorage can have a repressive affect on an image, as it will make the reader read an image as intended by the sender (Crow, 2010). In advertising, this might be beneficial, but when creating more ambiguous design, it seems like we should be careful with anchoring, in danger of being too literal in our communication.

Good design = durable design

Lastly I think rubbish theory was quite interesting, particularly in terms of how we treat our objects, which affects which theory the object belongs to (Crow, 2010). As we design, we are almost always trying to create durable design, and I guess the question of how we might do translates to the question of how we can create good design. What makes us keep some magazines and throw away others? And what makes some typefaces timeless, whilst other must suffer from becoming outdated?

Further research

Kenya Hara’s proposal for the Tokyo Olympics 2020

Inspired by Tom Finn’s analysis of the Olympic identities, I had a quick look at some that weren’t mentioned. In the process I discovered Kenya Hara’s proposal for the Tokyo Olympics 2020 (not the official identity). Having seen the one from 1964 (fig. 1), this identity feels like a beautiful modernisation of that. The gold type paired with red gradient circles are featured in both identities, but to me Hara’s feels more fluid and thus festive. The simplistic colour profile feels both elegant and confident, suiting the Olympic contestants.

Workshop challenge: process

Choosing a brand/story

Although this week’s workshop challenge seemed quite easy to me in the beginning, I ended up struggling with finding a brand/story to focus on. I started off by looking at IKEA as they have previously had catalogue in Israel and Saudi Arabia where the women have been taken out. I thought this would have been interesting to analyse in the light of IKEA branding itself as a typically Swedish brand (as Sweden has a social democratic society and I assume that it’s very untypical to support the views behind this action). However, I as I found out that IKEA has apologised, I thought this might be an outdated approach.

Further I was also interested in how book covers change across countries, which made me look at Harry Potter covers. Further, I was also intrigued by the brand Dr. Oetker, which in Italy is named Cameo, perhaps in order to seem more Italian. This could have been a nice brand to explore as it fits well with Barthes’ analysis of Panzani.

The problem with using Cameo/Dr. Oetker was that I felt as if it was a too literal response to the challenge. In the workshop challenge video, there seemed to be an encouragement for us to choose something abstract, and so I started thinking about recent global phenomenons. That’s when Black Lives Matter struck my mind. Although it is not a brand per se, BLM has been a large part of 2020 and I thought it could be interesting to analyse how the protests have been performed in different countries.

Visual references and a brief overview of BLM across the globe

In Vox-article “Black Lives Matter” has become a global rallying cry against racism and police brutality, Jen Kirby discusses the BLM protests around the world (Kirby, 2020). I decided to use this article, as well as the images as a basis for my analysis, I thought the article provided a clear overview of BLM across different countries.

Brussels

On June 7th Belgian protestors marched against the Police killing on American George Floyd (Kirby, 2020). The protests were against police brutality and racism, which is also a problem in Belgium due to their colonial history, but also their current inequities (Kirby, 2020). As well as marching with posters, the protestors vandalised a statue of King Leopold II also adding the flag of the Democratic republic of Congo (Kirby, 2020). Leopold II killed millions of Congolese people (Kirby, 2020).

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030026/GettyImages_1219052754.jpg)

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030029/GettyImages_1219053333.jpg)

United Kingdom

In the article, Kirby interviews a BLM UK organiser, who explains how BLM in Europe is both an action of solidarity with the police brutality and racism in the US, but also a response to the fact that racism also happens in the UK and in Europe (Kirby, 2020). In Bristol, protestors took down a statue of slave trader Edward Colston, which they spray painted and threw in the harbour (Kirby, 2020).

The mayor of London responded with a promise of investigating and removing signs and landmarks tied to slavery from the capital, leading to the removal of the statue of slave trader Robert Milligan (Kirby, 2020).

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030188/GettyImages_1218941064.jpg)

Kenya

Allegedly at least 15 people have been killed by police in Kenya for braking lockdown rules (Kirby, 2020). Thus, people also marched here (Kirby, 2020).

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030119/GettyImages_1218882728.jpg)

Brazil

There were also protestors for BLM in Brazil, fighting police brutality (Kirby, 2020). Their police killing statistics are one of the highest in the world (Kirby, 2020).

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030128/GettyImages_1218280663.jpg)

Syria

Aziz Asmar created a graffiti piece on a remains of a ruined building (Kirby, 2020).

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030155/GettyImages_1216879683.jpg)

United States

I will not try to summarise the whole BLM movement in the US. Instead I will focus the statues, keeping a red line through the various countries I’ve looked into so far. In America, many statues were broken or taken down by protestors (Bracelli, 2020). Statues of Christoffer Columbus across the country was spray painted or beheaded and several statues of previous presidents were taken down (Bracelli, 2020).

The symbolism of statues

In order to focus my case study, I decided to analyse the symbolic aspect of statues and the way protestors have vandalised statues of previous slave traders and racists as part of BLM. The vandalism has been done through very literal acts of symbolism, like spray painting statues red, tearing them down or braking them in some way. However, I think it could also be interesting to look at the statues themselves – what do they symbolise and why are they problematic?

I also think it will be interesting to analyse the differences in similarities in vandalism across countries. The way BLM spread across the world proved that racism is both a local and global problem, and the movement has definitely “worked” on a global level to quote this week’s brief.

Problem statement

In my text I will try to answer the problem statement: How is the message of Black Lives Matter symbolised through vandalism of statues at a global level?

I will focus on the US, the UK and Belgium as it seems like these countries are the ones where statue vandalism has happened the most during this year’s protests. In order to focus my text further, I have made a selection of statues as there have been performed vandalism or removal of such a large number of statues, particularly in the US.

How is the BLM symbolised through statue vandalism across countries?

What it means to attack a statue

Before I look at vandalism across countries, I will briefly discuss what it means to attack a statue. When we are attempting to attack or destroy the idea repressed by the statue, rather than simply arguing against it with words (Bromwich, 2020). Thus, vandalism against a statue can be seen as a symbolic attack on the ideas it represents.

To topple a statue

The toppling of the statue of Edward Ward in Nashville, US, could perhaps symbolise an enforcement of defeat, driven by the people of today. The physical force needed to take down a statue symbolises the strong will of the protestors. Thus the toppling could be seen as a symbol for the message of the protestors: that white supremacy and racism must fall, like the statues. Toppling of statues is not unique to the US. It was done to Edward Colton in the UK and King Leopold II in Belgium.

To sink a statue

Further, I will analyse the action of throwing something in the lake/harbour, done to one of the Christoffer Columbus statues in the US and to the Edward Colston statue in the UK (The New York Times, 2020). On a denotative level, one could say that this act might be performed in order to make it more difficult for the authorities to save the statue. On a connotative level, one could see it as a symbol of turning the statue into garbage, which I associate as the main object someone would throw into a lake.

To set fire to a statue

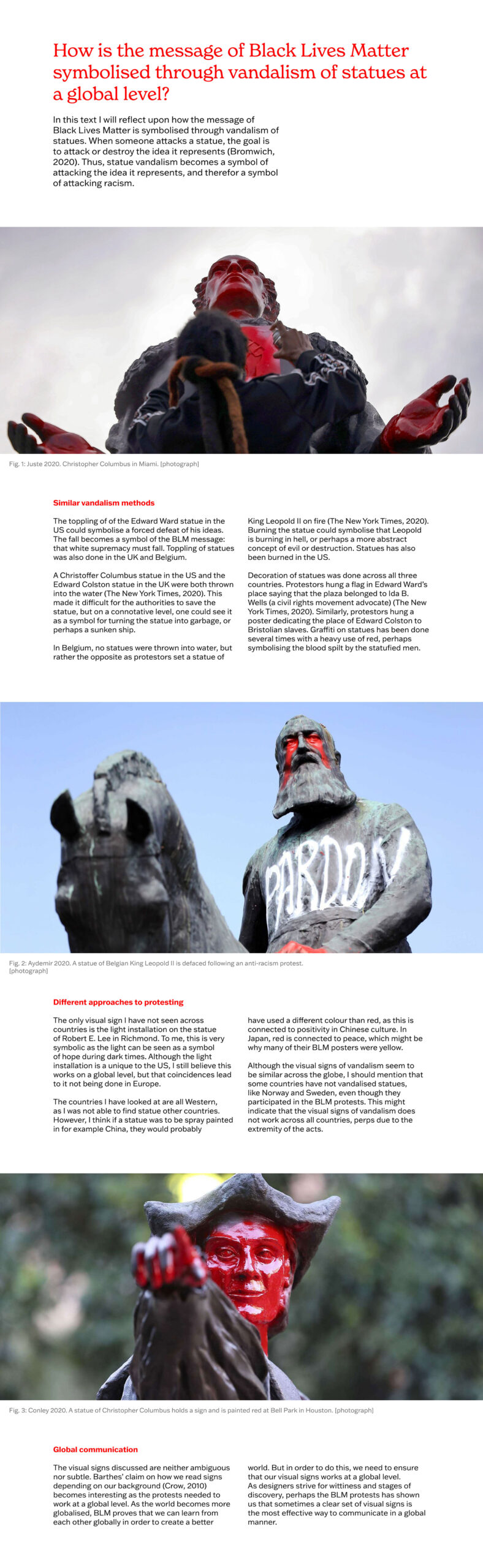

In Belgium, no statues were thrown into water, rather the opposite, as protestors set King Leopold II on fire (The New York Times, 2020). Burning the statue could symbolise that Leopold is burning in hell, or a more abstract concept of evil and destruction. This act was neither unique to one country as BLM protestors have also burned statues in the US.

To decorate a statue

Within a graphic design context, the act of spray painting and decorating (in lack of a better word) is perhaps the most familiar approach. Protestors hung a flag in Edward Ward’s place saying that the plaza belonged to Ida B. Wells (a journalist during the civil rights movement) (The New York Times, 2020). A similar act was performed in the place of Edward Colston in the UK as protestors hung a hand written poster dedicating the place to the slaves who built Bristol. Graffiti on statues was also performed across all three countries, with a heavy use of red, perhaps symbolising the blood spilt by the statufied men.

To light up a statue

The only visual symbol I have not been able to find across countries is the light installation on the statue of Robert E. Lee in Richmond. During the night, one could see the projected letters BLM, as well as an image of George Floyd (The New York Times, 2020). To me, this is very symbolic in terms of light and darkness as the light can be seen as a symbol of hope during dark times. Although this method is unique to the US, I still believe the message works on a global level, and that coincidences lead to it not being done in Europe.

Why might colour or typeface have been changed across countries?

In terms of changing colours and typefaces, I would like to comment on the hand written type and the obviousness of how it is bound to change across the world, but also from one protestor to another. In terms of colour, I have noticed a lot of red. My chosen countries are all in the west, as I was not able to find any eastern countries where statues have been vandalised. However, I think if a statue was to be spray painted in, for example China, they would probably have used a different colour as red is connected to positivity in Chinese culture.

Does it work at a local level and does it work at a global level?

I have not been able to find many differences across countries, but rather perhaps surprising similarities. The fact that people are willing to perform acts, that could be viewed as both extreme and dangerous, in order to get the message of BLM across, shows that racism is not only a problem in the US, but across the whole world.

However, I should also say that some countries have not vandalised statues, like Norway and Sweden, even though they participated in the BLM protests. And so the lack of vandalism in some countries might symbolise that the vandalism of statues does not work across countries. However, the reason behind this might also be that these countries do not have statues of previous slave owners as they were did not participate in colonisation.

Consider the impact the vandalism has on your understanding of visual signs and symbols

The various vandalism symbols are neither ambiguous nor subtle. They communicate a clear message that works at a global level. Barthes’ opinion on how we read signs depending on our background becomes interesting in this context (Crow, 2010). The symbolism used could not be culturally dependant as the protestors needed the message to work across the globe. Thus there needed to be a clear anchorage with texts, so that the readers would understand how to read the message.

As the world has become more globalised, we are not only able to spread global messages, but to learn from each other’s responses to global issues. But in order to do this, we need to ensure that our visual signs as global as well, thus perhaps leaving an argument for less ambiguity in our designs.

How is society manipulated by a message?

Although I do not believe we have been manipulated in the sense of being tricked into believing a lie, the vandalism on statues in the US have “manipulated” Europeans, as well as the global public, to question our historic figures and the ideas they represent. Through raw and bold visual signs, as well as dangerous performances (throwing statues in the water and setting fire to them) big parts of the global public has been forced to reflect upon previous historic views, as well as how they see the world and contemporary issues in both their local and global society.

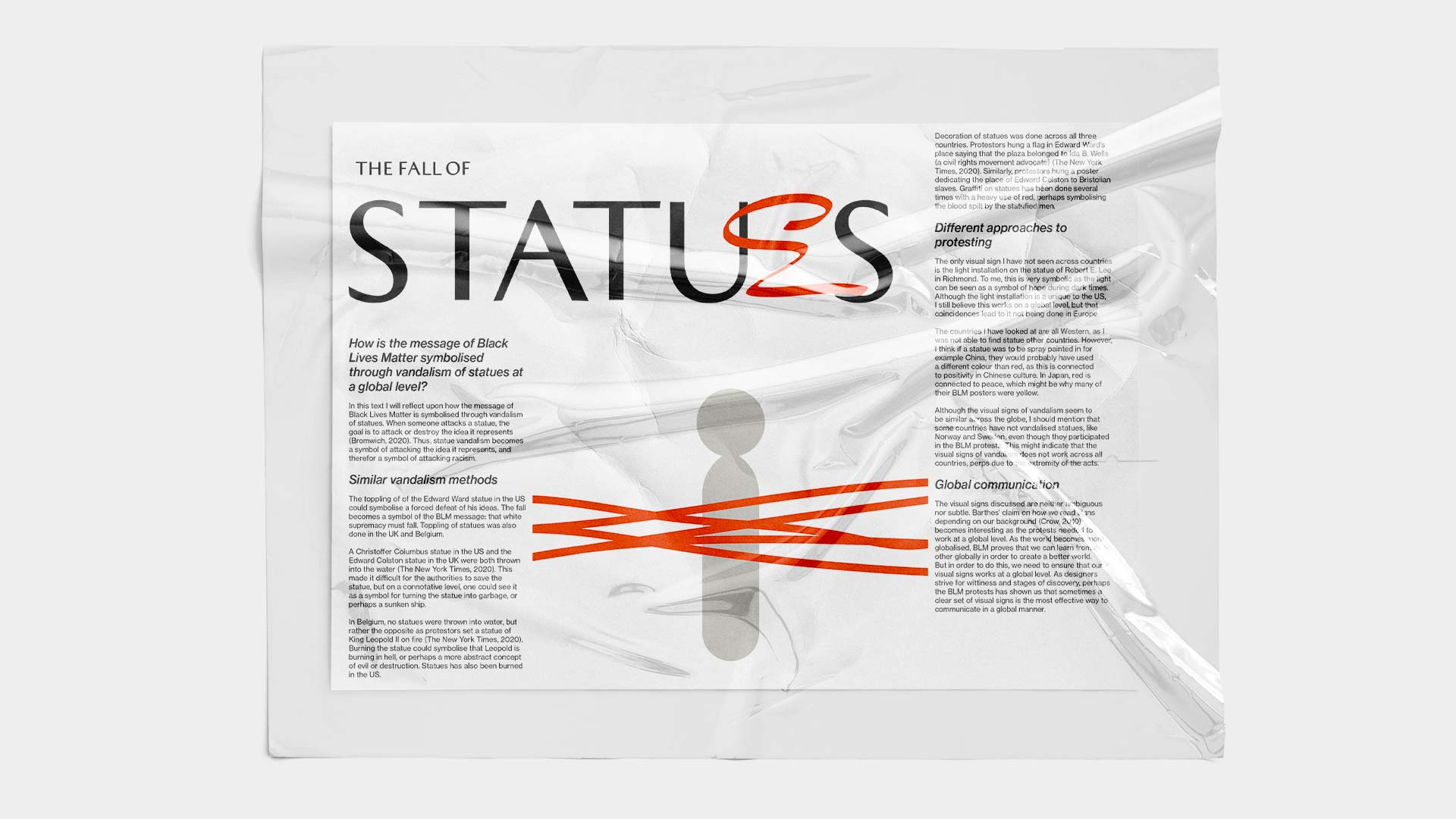

Workshop challenge: result

After analysing the vandalism on statues through the questions asked in the workshop challenge, I worked on my written material by shortening it down and choosing areas to focus on. I have used several of the points above and this is the final text I ended up with:

How is the message of Black Lives Matter symbolised through vandalism of statues at a global level?

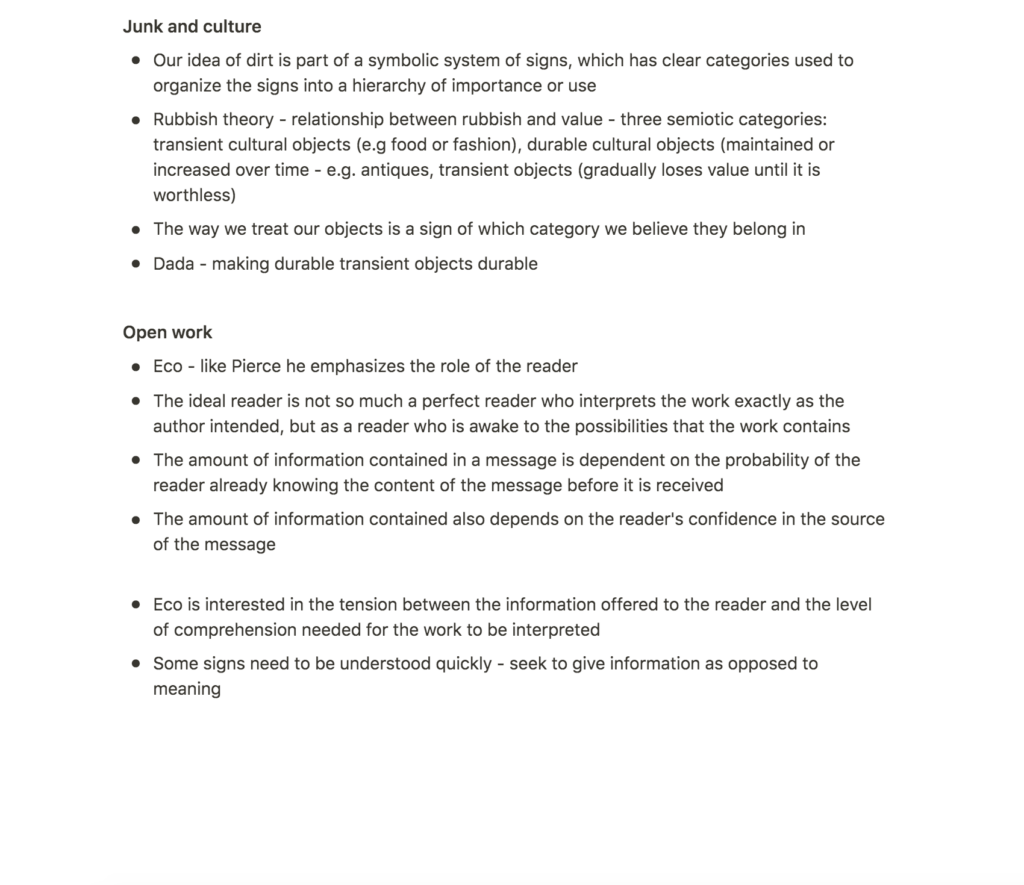

In this text I will reflect upon how the message of Black Lives Matter is symbolised through vandalism of statues. When someone attacks a statue, the goal is to attack or destroy the idea it represents (Bromwich, 2020). Thus, statue vandalism becomes a symbol of attacking the idea it represents, and therefor a symbol of attacking racism.

Similar vandalism methods

The toppling of of the Edward Ward statue in the US could symbolise a forced defeat of his ideas. The fall becomes a symbol of the BLM message: that white supremacy must fall. Toppling of statues was also done in the UK and Belgium.

A Christoffer Columbus statue in the US and the Edward Colston statue in the UK were both thrown into the water (The New York Times, 2020). This made it difficult for the authorities to save the statue, but on a connotative level, one could see it as a symbol for turning the statue into garbage, or perhaps a sunken ship.

In Belgium, no statues were thrown into water, but rather the opposite as protestors set a statue of King Leopold II on fire (The New York Times, 2020). Burning the statue could symbolise that Leopold is burning in hell, or perhaps a more abstract concept of evil or destruction. Statues has also been burned in the US.

Decoration of statues was done across all three countries. Protestors hung a flag in Edward Ward’s place saying that the plaza belonged to Ida B. Wells (a civil rights movement advocate) (The New York Times, 2020). Similarly, protestors hung a poster dedicating the place of Edward Colston to Bristolian slaves. Graffiti on statues has been done several times with a heavy use of red, perhaps symbolising the blood spilt by the statufied men.

Different approaches to protesting

The only visual sign I have not seen across countries is the light installation on the statue of Robert E. Lee in Richmond. To me, this is very symbolic as the light can be seen as a symbol of hope during dark times. Although the light installation is a unique to the US, I still believe this works on a global level, but that coincidences lead to it not being done in Europe.

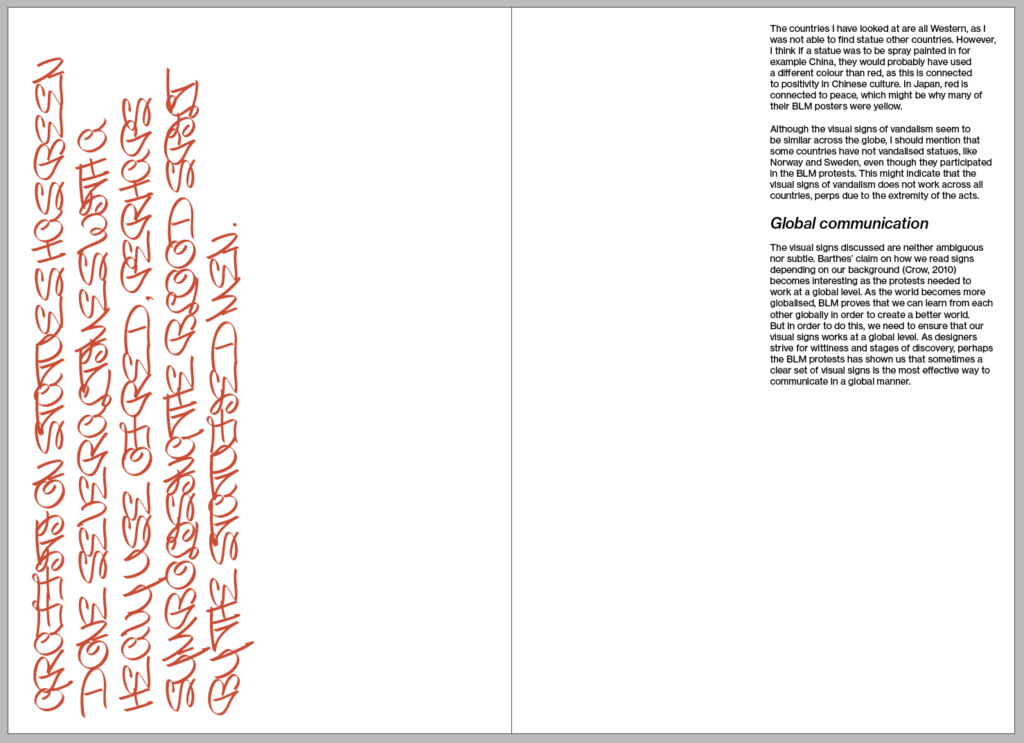

The countries I have looked at are all Western, as I was not able to find statue other countries. However, I think if a statue was to be spray painted in for example China, they would probably have used a different colour than red, as this is connected to positivity in Chinese culture. In Japan, red is connected to peace, which might be why many of their BLM posters were yellow.

Although the visual signs of vandalism seem to be similar across the globe, I should mention that some countries have not vandalised statues, like Norway and Sweden, even though they participated in the BLM protests. This might indicate that the visual signs of vandalism does not work across all countries, perps due to the extremity of the acts.

Global communication

The visual signs discussed are neither ambiguous nor subtle. Barthes’ claim on how we read signs depending on our background (Crow, 2010) becomes interesting as the protests needed to work at a global level. As the world becomes more globalised, BLM proves that we can learn from each other globally in order to create a better world. But in order to do this, we need to ensure that our visual signs works at a global level. As designers strive for wittiness and stages of discovery, perhaps the BLM protests has shown us that sometimes a clear set of visual signs is the most effective way to communicate in a global manner.

Visual process

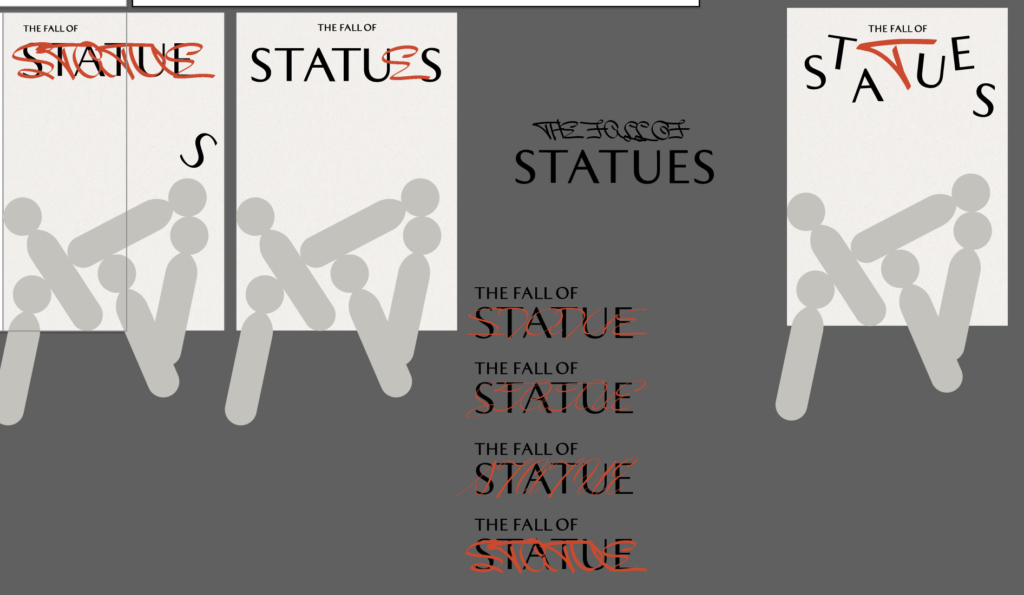

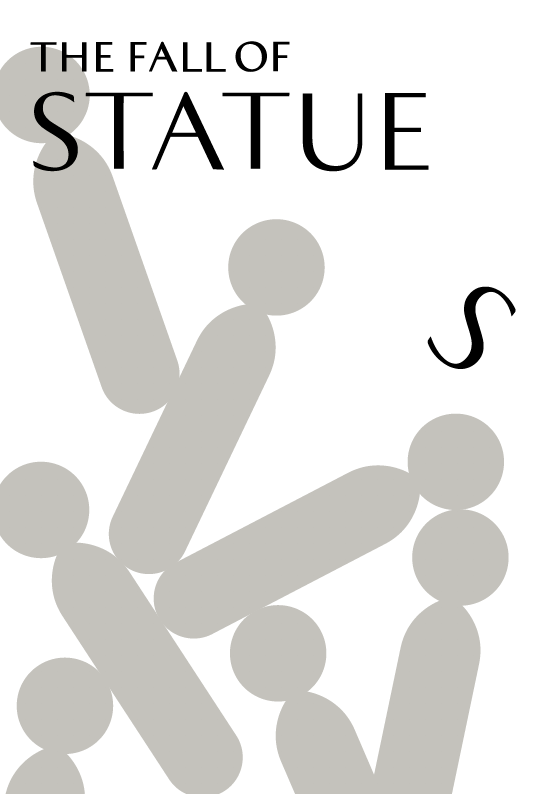

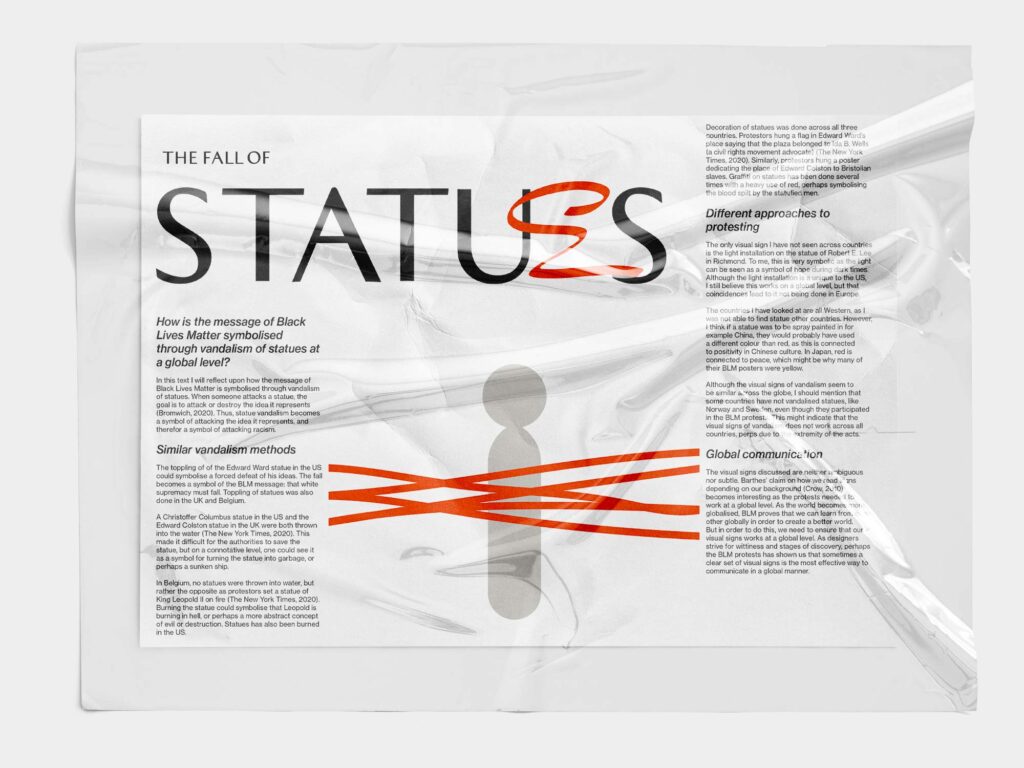

Unfortunately I didn’t notice that we were supposed to create an editorial this week, as it was only mentioned on the last page on Canvas and not in the brief. Thus, this was what I first ended up with:

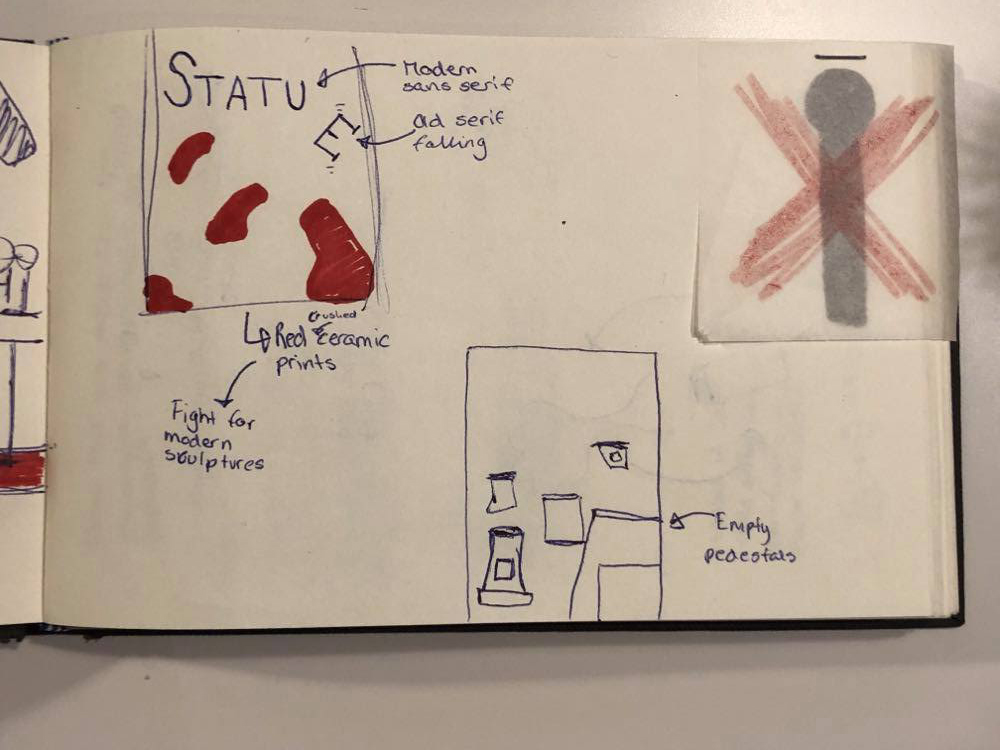

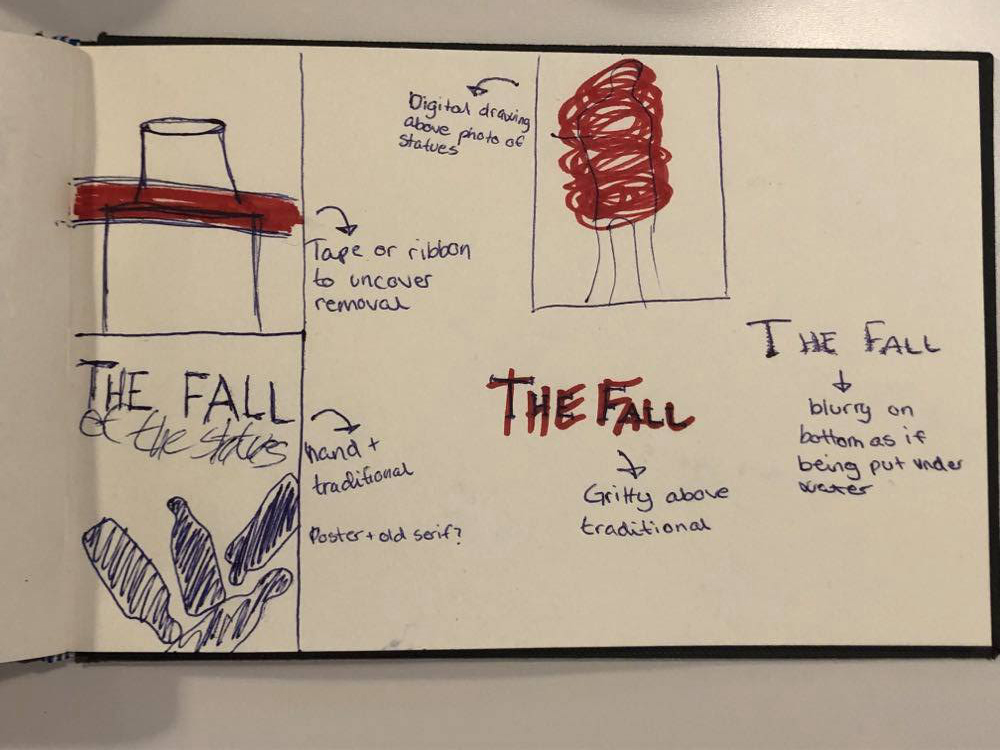

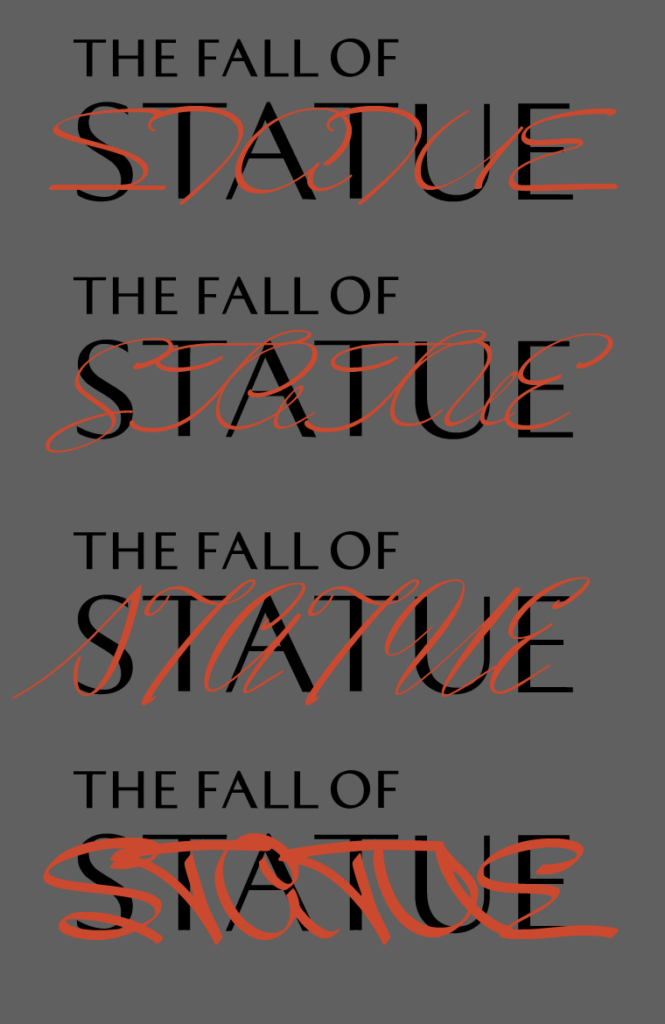

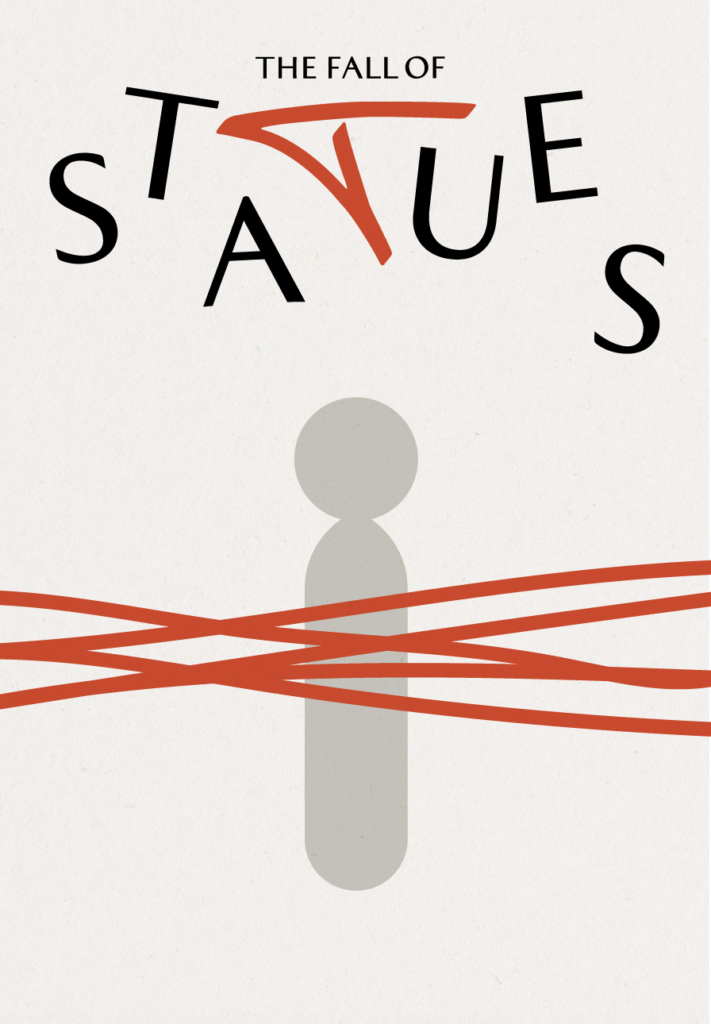

Luckily I found some time during week 12 to work further on my visual material. I wanted my visual editorial to be inspired by the vandalism methods performed to the statues. However, I didn’t want to simply spray-paint text, in fear of creating something too cliché. As I enjoy working with type, I thought it could be interesting to look at how one might use visual signs of typography as a way of communicating the message of my text.

The image above inspired my first ideas, both in terms of typography and vandalism symbols. I was intrigued to experiment with chopping off the serifs from an old serif typeface, both as a visual sign for the chopping of the statue’s head, but also as a symbol of getting rid of the old ideas the statues represent. Further I was interested in layering, as a symbol of how the protesters have used graffiti and posters to communicate their messages, layering their material above the original messages of the statues.

After a brief sketch session I started experimenting with typography and simple illustrations in illustrator and indesign. Garamond is one of the first serif typefaces I think about when thinking about old ideas and traditions. I therefor started experimenting with chopping it’s serifs, which gave me a similar result to what I had hoped for: classic letters with a modern twist to them. In order to include the graffiti element without being to cliché, I experimented with a variety of scripts that I thought resonated with graffiti, but that were not too raw edgy.

I quite liked the combination of typography, but still felt as if my design was missing the layering aspect. If I had more time, I would have started experimented with tactile approaches at this point, but unfortunately I had to settle for a mockup of physical layering this week. I was fortunate to find a mockup that illustrated similar layering to what I had explored in my sketchbook – a transparent element above a solid one. If I was to create this on my own, I would have experimented further with placing the red elements on the transparent layer and leaving the black on the normal paper. I also would have liked the two layers to work as one piece, perhaps attached at the top.

In conclusion

I have really enjoyed the material provided through the lectures and resources this week. I think semiotics can be quite interesting, especially when using it to analyse and pick apart imagery and design. Hearing about the different Olympics identities was great, as Finn’s analysis made me notice how small design elements contribute to a larger message.

Looking back, I might have been better off choosing an actual news story or brand for the workshop challenge, as analysing BLM vandalism of statues proved to be quite challenging. Instead of picking apart the reasoning for different colour and type choices, I’ve had to analyse more abstract visual signs, and I am not sure that I’ve managed to do so successfully.

I enjoyed working with typography for the workshop challenge, and I think my choice of chopping off serifs works well as a concept. Throughout the module I’ve struggled with setting type paragraphs in interesting ways, perhaps because I come from a photography background and have usually focused on imagery. However, this week I think I managed to create a somewhat successful layout that I am pleased with.

If I had more time I would have loved to explore further with the physicality of my editorial, especially with the layering. I like the result, but I think it would have worked even better if I had the freedom of making it myself, rather than using a mockup file.

REFERENCES:

Bracelli, P. (2020) ‘Black Lives Matter, what statues have been removed and why’, Lifegate [online], 1 July. Available at: https://www.lifegate.com/black-lives-matter-statues (Accessed: 2 December 2020).

Bromwich, J. E. (2020) ‘What Does It Mean to Tear Down a Statue?’, The New York Times [online], 11 June. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/11/style/confederate-statue-columbus-analysis.html?auth=login-google.

Crow, D. (2010) Visible signs: an introduction to semiotics in the visual arts. 2nd edn. London: AVA Publishing.

Edwards, S. and Thomas, P. (2020) ‘Breaking News 2.0 Installation at the London Design festival’. Canvas Falmouth Flexible [online], 27 November.

Finn, T. (2020) ‘Taking graphic design today and unpacking it. Take one story to see how it is reported globally’. Canvas Falmouth Flexible [online], 27 November.

Hosken, M. (2020) ‘The theory and symbolism behind a message’. Canvas Falmouth Flexible [online], 27 November.

Kirby, J. (2020) ‘”Black Lives Matter” has become a global rallying cry against racism and police brutality’, Vox [online], 12 June. Available at: https://www.vox.com/2020/6/12/21285244/black-lives-matter-global-protests-george-floyd-uk-belgium (Accessed: 2 December 2020).

The New York Times (2020) ‘How Statues Are Falling Around the World’, The New York Times, 24 June. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/us/confederate-statues-photos.html.

LIST OF FIGURES:

Figure 1. Masaru KATSUMI and Yusaku KAMEKURA. 1964. Tokyo Olympic Branding 1964 & Poster. Medium [online]. Available at: https://medium.com/@m_emmins/013-going-for-olympic-logo-gold-600e558bd0fa

Figure 2: Susanna EDWARDS and Patrick THOMAS 2020. Breaking News 2.0 Installation at the London Design festival. [lecture still]. Available at: https://flex.falmouth.ac.uk/courses/685/pages/week-11-lecture-parts-2-and-3?module_item_id=42778 [accessed 3 December 2020].

Figure 3. Kenya HARA. 2020. My first design proposal for the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games. Nippon Design Center [online]. Available at: https://www.ndc.co.jp/hara/en/olympic2020.html

Figure 4. IKEA. ca. 2008-2012. IKEA catalogue. [printed catalogue]. The Wall Street Journal [online]. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10000872396390444592404578030274200387136 [accessed 3 December 2020].

Figure 5. CAMEO. ca. 1984 – 2020. Ristorante Pizza Bianca Con Prosciutto e Patate Packaging. Cameo [online]. Available at: https://www.cameo.it/it-it/i-nostri-prodotti/pizza-ristorante/bianca-prosciutto-e-patate

Figure 6. Zheng HUANSONG. 2020. Demonstrators participate in a Black Lives Matter protest in Brussels, Belgium, on June 7. Vox [online]. Available at: https://www.vox.com/2020/6/12/21285244/black-lives-matter-global-protests-george-floyd-uk-belgium

Figure 7. Dursun AYDEMIR. 2020. A statue of Belgian King Leopold II is defaced following an anti-racism protest. Vox [online]. Available at: https://www.vox.com/2020/6/12/21285244/black-lives-matter-global-protests-george-floyd-uk-belgium

Figure 8. Unknown maker. 2020. No title. [photograph]. I News [online]. Available at: https://inews.co.uk/news/uk/edward-colston-statue-bristol-monument-pulled-down-historic-england-reinstated-440610 [accessed 3 December 2020].

Figure 9. Yui MOK. 2020. Workers prepare to take down a statue of slave owner Robert Milligan at West India Quay. Vox [online]. Available at: https://www.vox.com/2020/6/12/21285244/black-lives-matter-global-protests-george-floyd-uk-belgium

Figure 10. Patrick MEINHARDT. 2020. Cosmas Mutethia’s wife wears a mask with her husband’s name, who was killed by Kenyan police during a night curfew. Vox [online]. Available at: https://www.vox.com/2020/6/12/21285244/black-lives-matter-global-protests-george-floyd-uk-belgium

Figure 11. Buda MENDES. 2020. Protesters lie on the ground with a sign that reads in Portuguese “All Black Lives Matter” during a protest in Rio de Janeiro. Vox [online]. Available at: https://www.vox.com/2020/6/12/21285244/black-lives-matter-global-protests-george-floyd-uk-belgium

Figure 12. Izzeddin IDILBI. 2020. A graffiti artist paints a mural of George Floyd on a wall in Binnish district in Idlib province, Syria. Vox [online]. Available at: https://www.vox.com/2020/6/12/21285244/black-lives-matter-global-protests-george-floyd-uk-belgium

Figure 13. Tim BRADBURY. 2020. A statue depicting Christopher Columbus is seen with its head removed at Christopher Columbus Waterfront Park. Artnet news [online]. Available at: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/christopher-columbus-status-topple-1883958

Figure 14. Kimberlee KRUESI. 2020. Untitled. The New York Times [online]. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/us/confederate-statues-photos.html

Figure 15. Ben BIRCHALL. 2020. Edward Colston in Bristol on June 7. The New York Times [online]. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/us/confederate-statues-photos.html

Figure 16. Kenzo TRIBOUILLARD. 2020. Untitled. The New York Times [online]. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/us/confederate-statues-photos.html

Figure 17: Unknown maker. 2020. Protesters hang an ‘Ida B. Wells Plaza’ banner where a statue of Edward Carmack stood before it was toppled by protesters. . Available at : https://eu.tennessean.com/videos/news/2020/06/13/protesters-hang-ida-b-wells-plaza-banner-where-statue-edward-carmack-stood-before-toppled-protesters/3180915001/ [accessed 3 December 2020].

Figure 18. Brian PALMER. 2020. Untitled. The New York Times [online]. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/us/confederate-statues-photos.html

Figure 19: Ingrid REIGSTAD. 2020. How is the message of Black Lives Matter symbolised through vandalism of statues at a global level?. Private collection: Ingrid Reigstad.

Figure 20. Tim BRADBURY. 2020. A statue depicting Christopher Columbus is seen with its head removed at Christopher Columbus Waterfront Park. Artnet news [online]. Available at: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/christopher-columbus-status-topple-1883958

Figure 21. Unknown maker. 2020. No title. [photograph]. I News [online]. Available at: https://inews.co.uk/news/uk/edward-colston-statue-bristol-monument-pulled-down-historic-england-reinstated-440610 [accessed 3 December 2020].

Figure 22-28: Ingrid REIGSTAD. 2020. Workshop challenge experiments. Private collection: Ingrid Reigstad.

Figure 29: Ingrid REIGSTAD. 2020. The fall of Statues. Private collection: Ingrid Reigstad.

LIST OF FIGURES – FIRST ATTEMPT AT EDITORIAL:

Figure 1. Carl JUSTE. 2020. Christopher Columbus in Miami. The New York Times [online]. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/us/confederate-statues-photos.html

Figure 2. Dursun AYDEMIR. 2020. A statue of Belgian King Leopold II is defaced following an anti-racism protest. Vox [online]. Available at: https://www.vox.com/2020/6/12/21285244/black-lives-matter-global-protests-george-floyd-uk-belgium

Figure 3. Elizabeth CONLEY. 2020. A statue of Christopher Columbus holds a sign and is painted red at Bell Park in Houston. Chron [online]. Available at: https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/houston/article/Vandal-puts-blood-on-hands-head-of-15332407.php