Resource reflection

Skills and trends in today’s design field

One of the advice I received from my industry specialist was to investigate what skills employers are currently looking for, in order to prepare for graduation. Although I wouldn’t want to choose an outcome solely based on this, I’d be keen on learning sought after skills if relevant. In order to gain an understanding of sought after skills I visited various design blogs, in addition to reviewing trend investigations from the previous module.

Below are some of the sought after skills I would like to make part of my project.

Sought after design skills:

- Motion systems should be incorporated in visual identities from the start, and in this way inform the result holistically.

- Through co-design one should offer tools rather than solutions, blurring the lines between creator and consumer (Fjord, 2021)

- Consumers are looking for a sense of belonging through digital experiences (Fjord, 2021). This could be hugely relevant for my project, and it would be interesting to explore how people could feel a sense of belonging to Norway/Esperantujo through a digital tool.

Foundational skills that are lacking in my portfolio:

- Layout and publication design

- Print (packaging and material choices)

Steven Laporte: Ideal Language

In Steven Laporte’s article Ideal Language, the author discusses natural, constructed and ideal languages, highlighting the benefits of an ideal language, whilst also attempting to demonstrate how such a language does not (and perhaps can not) exist.

Laporte claims that although natural universal languages such as Latin and Italian have been successful in their ability to be universally understood, this success comes down to military and cultural domination (Laporte, 2018). Further he explains how natural languages “are never neutral because they are typically laden with the cultural values of their countries of origin” (Laporte, 2018). Saying this, Laporte demonstrates the need for a non-political universal language, which is not favoured by any of the speaking parties.

In his conclusion, Laporte explains how an ideal language aims to solve natural language issues such as ambiguity, lack of stability and universal acceptance (Laporte, 2018). The latter is perhaps the most relevant for Esperanto, as for the language to function as intended to, everyone would need to speak it. Therefore, an interesting approach in my project could be to increase the learning of Esperanto, perhaps by making it more accessible to the people of the world?

I do personally believe however, that the true value of Esperanto will always be (as with ideal language, like Laporte suggests (Laporte, 2018)) symbolic, enhancing the idea that it must be possible to find common ground across the world’s cultures. Simply bo choosing to learn Esperanto, one is performing a political (or perhaps non-political) act, expressing one’s wish to participate in neutral diplomatic communication.

Descartes on the possibility of a universal language

In a letter to Mersenne, the philosopher Descartes utters his views on the possibility of a successful universal language:

A universal language that would work at the level of the imagination, describing the actual “things” of the external world, could only produce uniform results in the perfection of Eden or the ideal of fiction. One should, instead, stick with the institution of geometry as a method of rationalizing nature, a divine language grounded upon the cogito’s transmission of being.

(Batchelor, 1999)

I think this quote demonstrates the bittersweet reality of constructed/ideal languages: that they can never really succeed in their aim. This becomes particularly interesting when referring to world peace or a complete global understanding for each other – there is reason to fight for it, but it can never really happen. The speculative notion this carries is something I’d like to pay attention to moving forward.

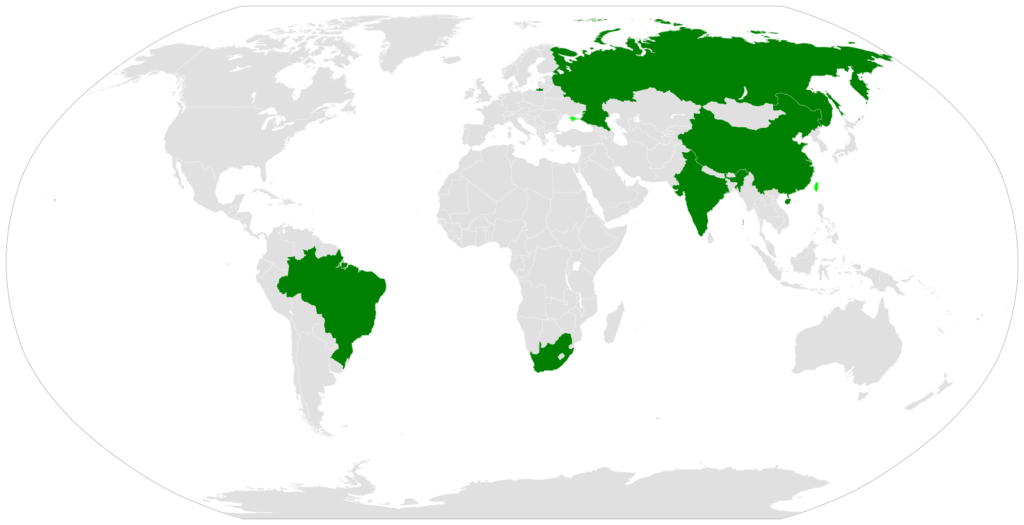

Esperanto as an Auxiliary Language and a Possible Solution to the BRICS Language Dilemma: A Case Study

In her article, Esperanto as an Auxiliary Language and a Possible Solution to the BRICS Language Dilemma: A Case Study, Byelongo Elisee Isheloke makes several arguments for the use of Esperanto as a democratic communication system between countries (Isheloke, 2019).

Making Esperanto part of the Norwegian school system

Firstly, Isheloke argues for Esperanto by highlighting how the language can be mastered within one year of learning (whilst French takes five and English seven) (Isheloke, 2019). Esperanto can also also be valuable in it’s ability to prepare students for further learning of foreign languages (Isheloke, 2019).

These facts made me wonder wether Esperanto could somehow become part of the (Norwegian) school system. In 8th grade, Norwegian school pupils have to choose a third language – usually French, Spanish or German. In my personal experience I’d say one hardly ever learns the language fluently (due to time limitation). Wouldn’t it then be better to learn a language that one might actually master within the time one has to learn it?

Making Esperanto part of the Norwegian school system could also signal how we as a country are willing to take a diplomatic stand, encouraging other countries to do the same.

Reducing economical cost

Isheloke further argues that having a shared language would be cost effective, as apposed to using costly translation services (Isheloke, 2019). I personally also imagine that using a shared language would save time and increase the general quality of communication.

Isheloke’s recommendations

As a conclusion, Isheloke recommends that South Africa (country in question in Isheloke’s study) should 1: “Experiment with Esperanto for a more democratic communication system between countries, and to avoid linguistic colonisation” (Isheloke, 2019), and 2; “Allocate more resources on BRICS economic initiatives including Esperanto teaching and learning in the long run” (Isheloke, 2019).

In other words, Isheloke presents Esperanto as a solution to avoiding linguistic colonisation, and recommends teaching and learning as a solution to language barrier issues. Adopting these aims (encourage “everyone” to learn Esperanto) could be an interesting and relevant approach for my project.

Redirection

After my decision of redirecting my project last week, I realised that I had to have re-think about my audience, project question and project aims.

I wasn’t able to do so fully this week, but in this document I attempted to reflect and ask myself relevant questions. Moving forward I will have to work out these questions in full.

Most importantly I will have to figure out wether my project’s main goal will be “to help Esperanto achieve it’s original aim”, “to increase communication and acceptance across cultures”, “to affect immigration policy makers”, or something else.

Weekly wrap up

Due to taking some time off this and last week (in return I’ll be working over the break), I haven’t been able to progress as fast as I would have liked to. This week for example, it would have been very beneficial to work further on my redirection document, in order to decide on new aims and a research question. That being said I do believe that solely focusing on reading and insight gathering has helped me stay open minded this week, pursuing texts I wouldn’t normally have prioritised.

Although I haven’t been able to make any revolutionary discoveries in this week’s reading, I’ve managed to find several pieces of literature that support my hypothesis and project foundation. These will be relevant as I go on to write my report.

Moving forward I hope to explore further literature as a way of gaining additional insight to what I already have – particularly in relation to Esperanto. Further, I hope to identify who my audience will be, and then what their wants and needs are. It would also be great to reach out to people within the Esperanto community, and perhaps a linguist who has specialised within constructed language. By doing so I would hopefully be able to gain a deeper understand of the language, as well as why people choose to learn it.

REFERENCES:

Batchelor, R. (1999) The Republic of Codes. Available at: https://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/writingscience/Cryptography.html (Accessed: 4 April 2022).

Fjord (2021) Fjord Trends 2021. Oslo: Fjord. Available at: https://www.accenture.com/us-en/insights/interactive/fjord-trends (Accessed: 5 November 2021).

Isheloke, B.E. (2019) ‘Esperanto as an Auxiliary Language and a Possible Solution to the BRICS Language Dilemma: A Case Study’, Respectus Philologicus, (36(41)), pp. 146–157. doi:10.15388/RESPECTUS.2019.36.41.30.

Laporte, S. (2018) Ideal language, ISKO. Available at: https://www.isko.org/cyclo/ideal_language.htm#3.2 (Accessed: 4 April 2022).

LIST OF FIGURES:

Figure 1. DIA STUDIO. 2015. Greg Sorensen. Behance [online]. Available at: https://www.behance.net/gallery/25286833/Greg-Sorensen

Figure 2. Frans HALS. Ca. 1649-1700. Portret van René Descartes. Wikipedia [online]. Available at:

Figure 3. Unknown maker. 2009. BRICS countries. [digital illustration]. Wikimedia Commons [online]. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BRICS.svg [accessed 4 April 2022].