Lecture notes

Lecture reflections

The power of listening

I enjoyed Jones’ discussions on approaches for his project The Cosmic Colliery. Jones’ way of interviewing (which he referred to as long conversations) seemed subtle as he mainly tried to guide the conversations, rather than interfere too much by stating opinion (Joe Pochodzaj and Hefin Jones, 2021). To me this method seems like a good approach if one wishes to understand the true reality of a user.

Further I found Jones and Pochodzaj’s conversations on methodology very interesting. They seemed to think that the design process should really emerge from the project, rather than the other way around (Joe Pochodzaj and Hefin Jones, 2021). As I go on to work with my project this week I will focus on listening and finding the essence of the project before establishing a process.

How can a project evolve when a designer leaves?

Jones’ idea of leaving a project fascinated me. By getting the local public to continue the conversations Jones started, he seems to have managed to create a sustainable project that can live on without him (Joe Pochodzaj and Hefin Jones, 2021). This is not only interesting in terms of conversations, but for design in general. How can we, for example, make sure that a brand keeps using a visual identity in an innovative way after we leave? Perhaps Jones’ way of transferring knowledge could be adapted. By establishing routines of workshops for the brand, one might be able to teach the brand how to evolve a visual identity on their own, even after you leave as a designer.

Resource notes

Resource reflections

The discussions on articulating values from the book Design Anthropology: Object Cultures in Transition, was interesting as I myself am eager to make my own values part of my work as a designer. By articulating one’s values (either as a brand or as a designer) one can analyse what we are doing and with whom, but also how our work is being used and what for (Alison Clarke, 2011).

As mentioned in the book, design consists of creating something new, and the consequences are not always clear as one does this (Alison Clarke, 2011). Thus, I wonder how designers could become better at mapping potential consequences that are not in line with one’s articulated values. Perhaps we could become better at testing prototypes and mapping future scenarios through critical design?

How to avoid green washing

Sustainable design is a big interest of mine, and I think it’s important to understand that what might seem sustainable and environmentally friendly isn’t always so. For example, buying a shirt made out of recycled fabrics is more sustainable than buying one made out of new fabrics. However, not buying it at all could potentially be better. So as a designer, I wonder wether or not it is “right” to create this recycled shirt if it contributes to people buying more shirts because one says that it is environmentally friendly to do so?

I think that by reflecting and being aware of potential consequences of one’s design, one might be able to stick to one’s values through understanding and learning as much as one can. As I go on to work with social issues, I hope to stay aware of ethical issues by reflecting upon the consequences of my solutions.

Workshop challenge

Topic: Local sustainable shopping in Oslo/Norway

As briefly touched upon above, I am eager to make personal values part of my work as a designer, and sustainability is a value that is very important to me. Sustainability holds a a number of subjects, but I decided to look at shopping as I myself have a big interest for fashion and clothes. Fashion is a big problem in terms of pollution, and greenwashing has made it hard to know wether or note one is buying sustainable clothes. Vintage shopping is therefor a great way of shopping sustainably, and I therefore decided to focus on issues with second hand shopping in Oslo and Norway today.

Process

Inspired by the lecture, I decided to keep my process plan quite loose in the early stages of the project. I therefore wanted to perform discussions/interviews with young shoppers in Oslo, and then use my findings from these interviews to inform the process onwards. As we only had a week to collect research, I also decided to look to the press for secondary interviews and video recordings in order to detect broader issues with sustainable shopping.

The Waste shock with Alexandra Joner

The Waste Shock (Sløsesjokket) is a Norwegian documentary series that looks at different types of waste in Norwegian society. In the episode about clothes and textiles, the show hos talks to musician Alexandra Joner, about the textile industry and the second hand scene in Norway today. When watching and analysing the show a variety of issues emerged:

- Ignorance is bliss

When Joner is first asked if she feels bad when buying clothes she replies instantly with a no (NRK, 2021). She then goes on to explain how it can be easier to close your eyes to injustice in order not to feel bad about your choices (NRK, 2021). It seems to me as if Joner knows that there is something bad about the textile and fashion industry, but by refusing to look into it, she continues to shop by staying ignorant. The fact that the public chooses to look away when faced with the environmental issues of fashion is a big issue that is definitely relevant to my topic of sustainable shopping. - Norwegians don’t buy enough second hand

As Joner and the show host goes to visit Fretex (Norways largest second hand shop and organisation), they learn that Fretex is the only organisation that collects used textiles on a large scale (NRK, 2021). However, they only use open 10% of the parcels, which they then only sell 20% of (NRK, 2021). Fretex explains this as a consequence of Norwegians not buying enough second hand clothes. - There is no national system for dealing with Fretex’s collections

Fretex is collecting way more textiles than they can handle and since they are not distributing textiles to other businesses, they ship 90% of what they receive to poorer countries (NRK, 2021). It is of course not clear wether this is a demand problem (businesses aren’t interested in using the rest of the 90%) or if it’s a distribution problem (Fretex does not have a sufficient distribution system that lets businesses use the rest of the 90%). If this is a demand problem, another issue is then that the fashion industry is not interested in using second hand textiles in their fashion lines.

Eilert Bjander: Wanting to shop whilst caring for the globe

In his article Mitt oppgjør med samvittigheten (My settlement with the conscience), Eilert Fredlund Bjander discusses how he has previously shopped for 30 000 NOK (about 3000 GBP) at Zalando because the retailer offers climate compensation (Eilert Fredlund Bjander, 2021). Bjander explains how he wants to be cool and clean by shopping and caring for the globe simultaneously (Eilert Fredlund Bjander, 2021). This article also highlights several issues with sustainable shopping:

- Greenwashing

Bjander moves on to reveal how climate compensation is not equal to being climate neutral. Thus, it is not actually sustainable to buy clothes from Zalando, it’s simply just better to buy climate compensation that not to. Rather than fixing the actual issue with the fashion industry (emissions, water usage etc.), Zalando had given their audience a quick fix which lets them stay ignorant to the textile industry issues. - Ignorance is bliss

Although Zalando might be partly to blame, Bjander, in the same way as Jones, chose to stay ignorant when shopping from Zalando, as he didn’t actually look into what climate compensation meant (until he eventually did of course). Thus, this article highlights one of the issues from The Waste Shock: that consumers choose to stay ignorant to the issues of fashion by not learning about the realities. - Misinformation

A consequence of greenwashing, besides encouraging people to buy unsustainable clothes, is that sustainably conscious people might become sceptical to the information provided by fashion brands – even if they had a sustainable business model. It can be hard to find information about actual sustainable shopping, and so one is left to consider a buy on ones own when one might not be educated enough to make an informed decision. The market is filled with retailers claiming to have sustainable garments, but how is the consumer supposed to know whether something is sustainable or not?

Live’s environment project: Consumption

In another TV show about the environment, Live Nelvik looks at the fashion industry in Norway with a focus on buying second hand and sewing/adjusting old clothes. This made me discover another issue, as well as a potential oportunity:

- A missing atmosphere

As Nelvik attempts to find used clothes she explains how she struggles to find nice second hand clothes (Live Nelvik, 2016). Further she says that she misses the atmosphere of shopping in a “normal” shop where the clothes are nicely displayed and there are scented candles around (Live Nelvik, 2016). Thus, it is perhaps not the idea of buying used clothes that is the issue, but the curation and experience of buying them. In a typical retail shop, clothes are displayed so that people will feel as if they “need” to buy them. In vintage shops in Oslo, the clothes are cramped together and one really has to know what one likes to find something. - Changing the mindset of young people

In the episode, Nelvik talks to Norwegian celebrity sewing personality, Jenny Skavland, who discusses the importance of making second hand clothes cool to young people (Live Nelvik, 2016). She states that when people buy second hand they will start to think of themselves as environmentally conscious, which will give them a mindset that they take with them into their careers and other areas of life (Live Nelvik, 2016). If Skavland’s insight is correct, making second hand clothing cool could be beneficial for the environment on an even larger scale than within the fashion industry.

Survey: What motivates Norwegians to buy second hand?

In a survey for OsloMet University’s science department (SIFO), Ingun Grimstad Klepp and Kirsi Laitala asked what motivates Norwegians to buy second hand (Sonja Balci, 2018). From the survey I’ve discovered the following issues:

- The biggest motivations for buying second hand are economy, the environment, and finding unique garments (Sonja Balci, 2018)

- 35% of those who only buys new clothes thinks second hand clothes feel dirty (18-24 year olds) (Sonja Balci, 2018)

I can personally understand why some might look at second hand clothes feel dirty. Clothes in second hand shops can be piled heavily, packed on tight racks, and they can also look quite wrinkled which could be associated with being dirty or unwashed. When buying online, you usually buy directly from the previous owner, which emphasises the notion of the garment being pre-worn (and one does not know how the garment has been treated before).

Interviews with young shoppers

Social circle interviews

In order to reveal the issues of vintage shopping in my local area I decided to talk to local shoppers with an interest in fashion. In the workshop challenge video we were encouraged to look beyond our social circles. However, I decided to ignore that encouragement at this point as I know several people who fit the description. In the previous brief I reached out to local communities for interviews, but unfortunately it was quite difficult to find people who were available in such a short time frame. I ended up considering the issues of interviewing friends smaller than the issues of not being able to find enough people to interview, and therefore decided to save some time by interviewing friends, in order to collect a larger volume of insight. Had my subject been sensitive or irrelevant for my social group I would of course have chosen a different group of people despite time restrictions.

I also reached out to Fretex (the largest second hand clothing organisation in Norway), but unfortunately they did reply and so I wasn’t able to interview anyone from the second hand market.

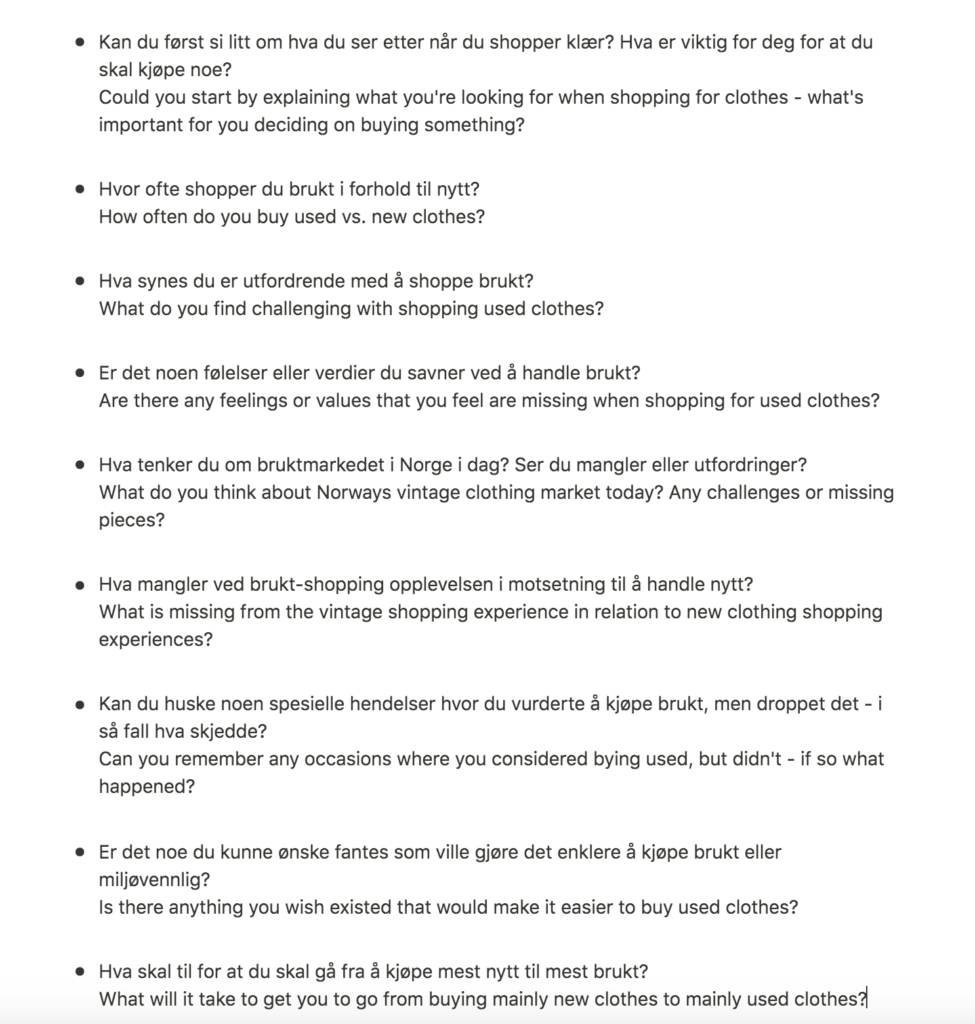

Interview guide

In preparation for my interviews, I created an interview guide by using the Service Design Tools website from last week’s material. I tried to create open questions which would reveal shopping preferences and issues with shopping second hand.

Since my interviews were in Norwegian, I will not post my interview notes, but rather a summary of key findings from each interview.

Shopper 1:

The first person I interviewed was a 25 year old woman living in Oslo, who buys about 60-70% of her clothes second hand. This is 40-50% more than the average Norwegian (Kjersti Lassen, 2020), which means that she had a lot of experience with second hand shopping. Thus, the Shopper 1 was able to provide insights on issues with the second hand shopping experience.

Key findings:

- Uncertainty and insecurity – Can’t know if an item will be the right size or fit when buying online (particularly jeans and trousers are difficult) and you can’t exchange clothes (difficult because you can’t try them on + because they are one of a kind and by waiting you risk someone else buying the garment)

- Sizing – particularly jeans and coats can often be too large

- Time consuming – When you need something specific or fast it’s easier to buy new as you’re “guaranteed” that you’ll find something (both in reference to size and type of garment)

- Lack of expertise/focus – Shops doesn’t focus on one area like jeans or pretty dresses – if there were second hand shops focused on specific things, one might be likely to think about that shop when in need of something particular

- Adventure – The fun part about second hand shopping today is the activity of finding treasures. You have to ask yourself if you actually like a garment or not.

*At the end of the interview I shared some personal insights, which means that I can not guarantee that point no. 3 and 4 was solely Shopper 1’s opinion (although she did state most of the content on her own). It did however lead to an interesting conversation that felt honest and informative.

Shopper 2

Shopper 2 is a 25 year old woman living in Oslo who buys mainly new clothes. When she does buy second, she usually looks for unique items that are sold out in the new-clothes-market or that have gone out of production. She is fashion-oriented and likes to come up with looks in her head, and so she often finds herself looking for particular items when shopping (often online). With a lack of a better word I would describe her as a “fashionista”. She is positive to second hand shopping, but rarely does it. Thus, Shopper 2 was able to provide several issues with Norway’s second hand market, which keeps her from buying more second hand today.

Key findings:

- A brand needs to be top of mind – When shopping online at e.g. Zalando, she searches for brands which she knows that she likes. She can sometimes buy second hand from Tise (similar to Depop), but that is usually if she is looking for an item that has gone out of production or is sold out in new stores.

- Bad value for money – The stock usually consists of fast fashion brands from a few years back (with the trends from that year). They are priced too high compared to the clothes’ value. Also hard to find “gems”, which she would be willing to pay more for. Today it’s cheaper to buy new than second hand.

- Availability / poor UX – New clothes are easy to buy (free returns and deliveries, can try things on at home and easy to find what you’re looking for). Hard to find something that is not only your personal style, but also the right size (particularly jeans and trousers). If she’s going to buy more second hand the experience needs to become easier and the must be a wider selection of garments. Today second hand shopping takes too much time.

- Uninviting stores / poor sales and branding strategies – The fitting rooms are uninviting and the shops have branding that she doesn’t relate to. She can’t see a visual merchandising focus and she doesn’t want to browse unless she needs something particular.

- The value of a reward – Mentions the valuable feeling of falling in love with a unique garment: “When you do find the correct fit and personal style it’s as if it’s meant to be”. She thinks it’s trendy to shop second hand – “when shopping at Robot (local vintage shop) you’re willing to pay more because you get the trendy tote bag that everyone else ownes”.

- Few people in large geographical areas – “Because of Norway’s geography I think it’s easier for those outside of the big city to shop online”.

Shopper 3

The third shopper is a 26 year old woman living in Bergen (second largest city of Norway). She used to live in London, which means that she was able to compare the Norwegian second hand scene to a more developed and international one. Today she buys about 10% of her clothes second hand, but she bought more when living abroad. When shopping she mainly looks for timeless high-quality garments as she wants to build a small wardrobe that can live on for a long time.

Key findings:

- Poor branding and sales strategies – She mentions how Arket is the love of her life – “They have high quality clothes and they put a lot of love into their clothes”. In second hand shops she doesn’t feel like the garments have been cared for. In the UK she looked at second hand shops as unique shops (as a brand), in Norway she only sees second hand shops as charity shops, rather than unique brands. When passing second hand shopping windows in the UK she would think “Oh I could wear that”, whilst in Norway she finds the shops dull and sad. The second hand shops lies in different locations than the high street – next to warehouses, rather than at the mall, which contributes to them not feeling like a “normal shop”.

- Availability – Little to choose from – she wants to know that there’s a chance she’ll find something when entering the store. Today she feels like she’s spending time looking for something that doesn’t exist. Also hard to find good pieces on Tise because you have to browse through so much.

- Lack og professionalism – A large part of the second hand market in Norway consists of individual sellers (which means no returns, can’t try the clothes unless you do so in someone’s kitchen, people suddenly sell their garments to someone else). In the shops there is no customer service (no one is asking what you’re looking for etc.) and you don’t know the story of the clothes and wether they’ve been repaired and cared for by the shop owners. “I don’t feel confident that Fretex sterilises their clothes or that the garments are of good quality”.

- Negatively loaded USPs – She thinks the main argument in Norway for buying second hand clothes, is fixing heavy issues related to the environment. This can be hard to relate to because there are so many problems in the world. She’s missing a focus on how fun second hand clothes can be: “Can’t it be more fun? Perhaps by focusing on the joy of wearing you’re mother’s old clothes?”

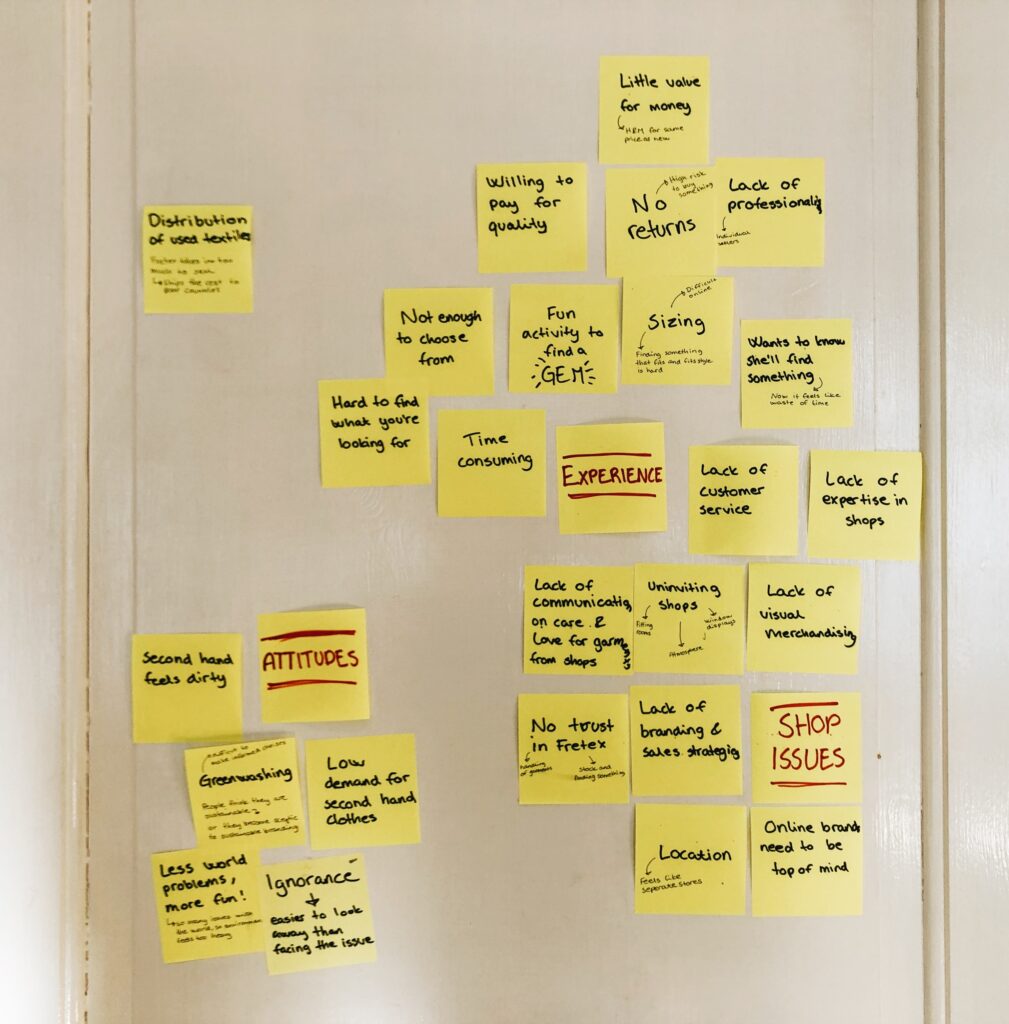

Synthesis Wall: clustering important insights

In order to cluster and process my various insights, I attempted to build a synthesis wall (using the Service Design Tools website as a guide). This was very valuable as it made me realise that the majority of my interview insights relates to issues with the second hand shopping experience. The wall also made me discover an interesting issue: Fretex (Norwegian charity shop organisation) is saying that the reason they only open 10% of what they receive is due to low demand – however, the insights from my interviews makes it seem as if there are not enough second hand clothes to choose from in the shops.

By using the synthesis wall, I’ve narrowed my research down to the following key issues:

- Shopping experience: it’s time consuming and difficult to shop second hand

The lack of free deliveries and returns, as well as garments being one of a kind makes online second hand shopping a high risk activity. It is also time consuming and demanding to find what you’re looking for (both online and in shops). Finding something that suits your personal style, which is also the right size and fit is difficult (particularly when it comes to jeans). Customers want to be confident that they’ll find something when entering a shop, but today they feel like they might be wasting their time and that they’re looking for something they won’t find. Interviewees also seem to feel like second hand shops caries a lot of dated fast fashion brands (little value for money). - Brand communication: Lack of professionalism and expertise

Since a large part of the second hand market consists of individuals rather than businesses, the second hand market is unprofessional. When you do visit a second hand shop, there is a lack of customer service and the shop owners don’t have (or they don’t communicate) enough expertise and care for their garments. The shops are uninviting and there doesn’t seem to be much branding or visual merchandising strategies in place. Second hand shops mainly come off as second hand shops, rather than unique brands.

Project Brief

The majority of my gathered insights focuses on user’s issues with second hand shopping, which mostly revolve around the shopping experience. The three shoppers I’ve interviewed all seemed open to shop second hand clothes, but what seemed to stop them was a combination of it being difficult, time consuming and poorly executed in terms of branding and expertise. Rather than focusing on attitudes towards second hand shopping (for example by through an awareness campaign), I have therefor chosen to focus on the customer experience issue of shopping second hand i Norway today. Since Norway’s population is quite small in relation to it’s physical size, I decided on a digital focus (although depending on my solution, the service might have the potential to expand into a physical service as well).

Brief:

How can we make second hand shopping appealing to young Norwegians across digital surfaces?

Today, Norwegian consumers face a high risk when shopping second hand clothes online. A large part of the market consists of individuals, rather th an businesses, which means that there is a lack of professionalism and customer service. Consumers find it time consuming to look for suitable garments, and the lack of decent return policies are stopping young people from taking the chance on one-of-a-kind garments (which are likely to be gone by the time they go shopping again). In the abundance of clothes, customers are struggling to find pieces which suits their personal style, size and fit preferences, which also leads to them reporting on the selection being too narrow. Some of the interviewees feel like they’re wasting their time, as they don’t believe they’ll be able to find relevant garments.

Norway’s largest second hand organisation, Fretex, is owned by the Salvation Army and there seems to be a lack of trust from consumers in their expertise and care for the garments. Fretex’s branding focuses on providing cheap clothes for those in need, yet consumers seem to think that Fretex offers little value for money. The shoppers from my interviews find Norway’s second hand shops uninviting, which might be due to lack of branding and sales strategies. Rather than being seen as individual brands, second hand shops are mainly seen as charity shops, rather than just shops. This contributes to failure (or lack of communication) in shops’ expertise, focus, style and customer service.

Visual summary

Since I’ve spent a lot of my time researching this week, there wasn’t much time left to create an innovative visual summary. I therefore decided to keep it simple by making a minimal presentation that features my final brief and key information about the detected issues. I’ve used two shades of green to represent the environment. My main aim however, was to create a current design that differs from the dull second hand shops in Norway today. I have used a characteristic typeface for my headings for the design to stand out, and contemporary clean lines in my pictograms to represent modern consumers. Next week I’m hoping to put more effort into the visual aspect of my project as I start to develop a concept for the service, as well as a branding system.

Fig. 5: Reigstad 2021. Brief: How can we make second hand shopping appealing to young Norwegians across digital surfaces?

The photographs used in this work were collected from websites with a creative commons license, and were not created by me.

In conclusion

I have really enjoyed unpacking the issues of second hand shopping this week. Working with a topic that I’m passionate about has inspired me, and so has this week’s process. Inspired by the lecture, I decided to focus on listening to conversations and let what I heard guide the project onwards. This way of working has been so rewarding and the interviews in particular has provided me with loads of insight that I wouldn’t have come up with on my own.

Unfortunately I wasn’t able to develop a proper concept for my visual summary due to time restrictions. However, I wouldn’t have spent less time on research if I was to do the week over, as I think the insight will contribute a lot to the final service design. If I had more time though, I would have liked to develop a more innovative design for the presentation, perhaps by linking my visual aesthetic to the insights in a better way.

The workshop challenge video this week encouraged us to interview people outside of our social circle. Yet, I think with my chosen topic, interviewing friends has been very beneficial. I’ve been able to perform 3 interviews in a week, and since there was a personal connection, it felt as if the interviewees could open up to me and speak freely. Since I know quite a lot about their shopping habits I felt as if I understood their answers, and I also saved time on collecting background information.

I am quite happy with my established issues of second hand shopping. The only potential problem is that the project might become a bit too large for one week. Therefore, I think it will be important to keep a tight schedule next week to make sure that I am able to develop a user centred service which also appeals to youth in terms of branding. I am really excited to start designing my service and as me move on with the course I would like to take with me the user centred way of researching that I have used this week.

REFERENCES:

Alison Clarke (2011) Design Anthropology: Object Cultures in Transition. London: Bloomsbury.

Eilert Fredlund Bjander (2021) ‘Mitt oppgjør med samvittigheten’, NRK, 13 March. Available at: https://www.nrk.no/klima/xl/hva-skjer-nar-jeg-klimakompenserer-hos-zalando_-1.15361309 (Accessed: 12 April 2021).

Joe Pochodzaj and Hefin Jones (2021) ‘Research and Reveal: Develop Key Finding, Analysis and Objectives’. Canvas Falmouth Flexible [online], 9 April.

Kjersti Lassen (2020) ‘Gjenbruk av klær er ikke så vanlig som du tror’, Oslo Met: Forskningsnyheter, 26 May. Available at: https://www.oslomet.no/forskning/forskningsnyheter/gjenbruk-av-kler-ikke-sa-vanlig-som-du-tror (Accessed: 13 April 2021).

Live Nelvik (2016) ‘Forbruk’, Lives miljøprosjekt. NRK. Available at: https://www.nrk.no/skole/?page=search&q=shopping&mediaId=21749 (Accessed: 12 April 2021).

NRK (2021) ‘Alexandra Joners klessjokk’, Sløsesjokket. NRK. Available at: https://tv.nrk.no/serie/sloesesjokket/sesong/1/episode/2/avspiller (Accessed: 12 April 2021).

Sonja Balci (2018) ‘Unge er mest skeptisk til gjenbruk’, Forskning.no, 15 November. Available at: https://forskning.no/forbruk-oslomet-partner/unge-er-mest-skeptisk-til-gjenbruk/1260031 (Accessed: 13 April 2021).

LIST OF FIGURES:

Figure 1. Unknown maker. 2015. Cosmic Colliery. [coloured photograph]. Hefin Jones [online]. Available at: http://hefinjones.co.uk/cosmic-colliery [accessed 15 April 2021].

Figure 2: NRK. 2021. Alexandra Joners klessjokk. [TV-show still]. Available at : https://tv.nrk.no/serie/sloesesjokket/sesong/1/episode/2/avspiller [accessed 15 April 2021].

Figure 3. Ronald Hole FOSSÅSKARET. 2021. Le Repas Frugal. NRK [online]. Available at: https://www.nrk.no/klima/xl/hva-skjer-nar-jeg-klimakompenserer-hos-zalando_-1.15361309

Figure 4: NRK. 2016. Lives miljøprosjekt 4: Forbruk. [TV-show still]. Available at : https://www.nrk.no/skole/?page=search&q=shopping&mediaId=21749 [accessed 15 April 2021].

Figure 5: Ingrid REIGSTAD. 2021. Brief: How can we make second hand shopping appealing to young Norwegians across digital surfaces?. Private collection: Ingrid Reigstad.